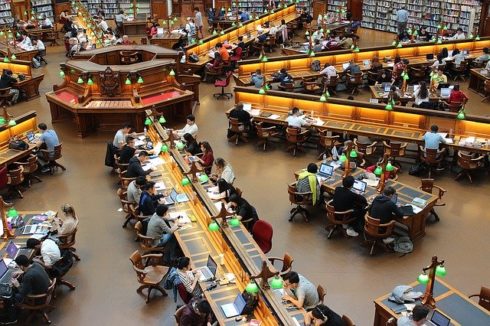

Academic data is one of the most underutilized forms of data that exist today. Outside of educational institutions, the only significant use of this data is in enrollment verification, though even that use case is not particularly widespread. And yet, academic data holds massive potential in providing predictive behavioral signals that could directly benefit the owners of that data: students and graduates, most of whom have very little other data they can point to when interfacing with employers, lenders, insurance providers or other businesses.

Academic data represents 25% of an individual’s lifetime. So, why is this data invisible to the world outside the educational market? The answer to this question may lie in the story of another data class that over the last 20 years went from being “invisible” to ubiquitous in modern products and services: personal banking data.

It may be hard to imagine today, but in the late 1990’s customer bank account data was viewed as owned by the bank, for the bank, to be shared with other institutions for the sole purpose of the bank, so that consumer access and use was tightly held within the confines of bank services. The closest thing we had to open access via APIs (let’s use that term sparingly) were technologies such as SWIFT and ACH, which were primarily focused on inter-institutional data exchange.

With the advent of the internet, banks still maintained that same protectiveness around their customer data, lagging most other industries in democratizing access to information. Consumers could view their banking data online — but only within the confines of the bank’s own web site. The limited accessibility was partially motivated by technical limitations, but more so by a view that the bank knew best what the consumer wanted, and that exposing consumer data externally would somehow risk that consumer’s relationship to the bank.

The result of this insular attitude towards data ownership was that innovative consumer products and services could only come from the banks. In other words, they didn’t exist.

In the world of today, where almost every type of financial service can be obtained within the palm of our hand, it may be hard to imagine a world with no online payments, no personal finance sites, no online lending, all of whom rely on some form of bank account data to power their customer experiences.

A closer look at the accessibility and technologies related to academic data shows many parallels with the story of banking data. Instead of banks, we have academic institutions inwardly focused, holding to a data policy that serves the institution rather than the student or alumni. As the banks did a generation ago, academic institutions are more concerned with the internal business of the institution than enabling innovative products and services that would benefit students and alumni. Anyone having to produce a transcript in a job application or background check knows the pain — and cost — associated with the experience.

Twenty-five years ago — no one could have imagined the financial applications and services that we now take for granted, all of which were enabled as a result of the efforts of a handful of companies that unlocked the potential of bank data by building API platforms that made financial data available to outside software developers. Companies like Yodlee, VerticalOne, and, more recently, Plaid have unleashed a wave of innovation that continues to this day by providing access points to previously inaccessible data.

The common thread with these companies is that they built consumer-centric rather than institution-centric experiences. The consumer chose to share their data with the product or service provider rather than relying on the bank to supply the service.

Academic data is in desperate need of the same enabling infrastructure as personal banking data. Transcript data represent a significant — and yet still invisible — measure of achievement, one that is ripe with insights that could directly benefit young adults, particularly those in the age range of 18-27, who comprise the $100 billion emerging consumer category.

The market is already embracing alternative data sources in lending; one of the big three credit bureaus, Equifax, announced earlier this year that it will give customers the opportunity to provide lenders their electric, phone and cable payment information, embracing the use of alternative metrics to help determine their worthiness for a loan – and potentially expand the pool of approved borrowers. Companies like Goldman Sachs, Ally Financial, Discover Financial Services as well as upstart fintech firms are also incorporating new data sources to make lending decisions. Yet, academic data largely remains an untapped resource for consumer insights, which I believe can extend much further than today’s early efforts.

What would a world look like if students and alumni could easily share their data with businesses to enable innovation to better service these consumers? What types of innovative products or services would result? A few motivating thoughts come to mind:

- Education: Increasing the number of non-degreed students with a two-year degree by getting credit for the course work taken in a four-year degree program

- Employment: Using academic achievements in people analytics to enhance talent acquisition and development strategies and execution driving a more successful relationship between employers and employees.

- Financial Services: Expanding financial products such as private student loans, student credit cards or maybe more appropriate security deposits on apartment rentals by linking academic achievements to credit performance versus using data that is based on limited work or no to limited credit history

- Insurance: Leveraging academic achievements for underwriting insurance products for students and recent graduates driving higher lifetime value.

No one could have predicted the panoply of services and products that resulted from unlocking bank data. Given academic data’s strong predictive signals for young consumers with limited financial history, the potential for new products and services are seemingly unlimited. The opportunity for businesses to access this data would be a more meaningful interaction early in the consumer lifecycle, as well as an opportunity for young adults to receive benefits never before available to them. I believe the time has come to build the necessary systems and technologies to unlock one of the last great untapped sources of data and unleash its potential.