Everyone seems to be talking about DevOps but, if you are new to it, it might all seem a little overwhelming. For an organization that doesn’t use DevOps today, the adoption of this three-step approach will promise a generally clean implementation.

Step 1: Creating the Application Pipeline

Regardless of the type of application, the pipeline looks very similar. The goal is to weave application releases into a new coordinated process that looks something like this:

- The developer makes changes locally to their laptop/PC/Mac, and upon completion (including their testing etc.) issues a Pull Request.

- Code-review kicks in now and the developer changes are reviewed, accepted, and a new release can be created.

- Someone, or the system, runs a procedure to create a Release Artifact, which could be a Java JAR file, a Docker File, or any other kind of Unit of Deployment.

- Someone, or the system, copies the artifact to the web or application servers and restarts the instances.

- Database migrations/updates may be additionally applied, although the database is often left outside of the application release process.

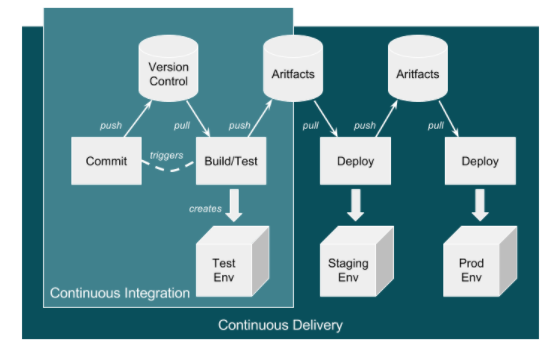

This process evolves into an automated application-only continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipeline by using a toolset to automate the process as shown in the diagram below:

A Typical CI/CD Pipeline. Source: https://ukcloud.pro/

However, be aware that this isn’t ideal (yet), because at this point the application alone is being released (injected) into existing environments.

If the developer has altered the local environment as well as the application, but these local environment changes are not part of the release, then they’re not in version control. And, if they are not applied at the same time as the application, then the application will break. The solution is for application and infrastructure releases to be synced.

Step 2: Creating the Infrastructure Pipeline

Ideally, the infrastructure team has learned from the developer team’s DevOps and CI/CD pipeline journey and can expand and adapt it for the infrastructure (which increasingly is a public cloud).

There are some differences with the infrastructure pipeline, specifically around units of deployment that are now the infrastructure layers in environments, the things that surround an application such as the DNS, load balancers, the virtual machines and/or containers, databases, and a plethora of other complex and interconnected components.

The big difference here is that the infrastructure is no longer described in a Visio diagram: it is brought to life in code, in a configuration file, in version control – this is Infrastructure as Code (IAC).

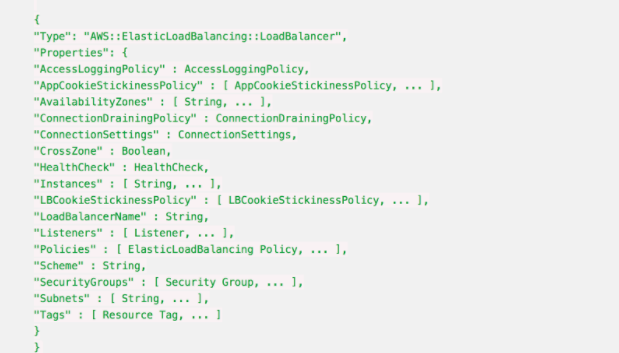

Before this, a load balancer was described in Visio diagrams, Word documents, and Excel spreadsheets of IPs and configurations. This is now swapped to describing everything about the load balancer in a configuration file.

Here’s an example AWS CloudFormation configuration for a load balancer:

Whenever this file is changed in Version Control, such as changing the subnets a load balancer can point to, then the automation engine can update an existing infrastructure environment to reflect that one change, and any dependencies that change.

It also means that you can apply this template to multiple environments, and be very confident that all environments are consistent.

It is also possible to make the templates dynamic to change their behavior according to the environment, so in production the environment will scale out across three datacenters, but on a developer’s laptop it will use a local VirtualBox single-system.

Step 3: Creating the Full Stack Pipeline

The goal of a full-stack pipeline is to ensure that the application and infrastructure changes over time are in sync, both in version control and the release deployments across each pipeline stage.

The popular CI/CD tools can now automate the full stack because everything is programmable. This means everything can be captured in version control, and the same configuration can use dynamic input parameters to build an environment on a developer’s laptop, or a QA system in the cloud, or updates to production.

Imagine a developer makes an application change that also requires a change to the database, to the web instance scaling configuration, and to the DNS. All of these changes are captured in one version control branch and the developer builds a system on their laptop from this branch, and tests it.

This is what Platform-as-a-Service systems can do. By adding an environment configuration file inside the same code base as your application, you can ensure that you have bound your application to the infrastructure.