I’m calling it now. Keeping in mind while I do this that I have been fabulously wrong in my predictions before, I am now, as we speak, calling this the peak. The bubble might get a little bigger, but it’s coming time for it to pop.

Again, I’ve been very wrong before. I called tablets a fad, and I was a firm believer in Eucalyptus, which was recently sold to HP at what I hear was essentially a fire-sale price. I also once predicted the Sega Dreamcast would outlive the Sony PlayStation 2. (Of course, the homebrew world may prove me right in a couple decades, but that’s another story entirely.)

I’ve been through this cycle before, and a lot of you have too. Back when the first tech bubble was inflating in 1999, high-ranking editorialists around the world opined that this wasn’t a bubble, but rather a long boom. Futurists predicted the end of work, the rise of the Internet, and the elimination of old-world traditions in business. B2B was the next big thing, and RFID tags were going to change the world. Linux was the new Windows, the Web was the new paper, and venture capital investments were the new student loans.

And then it burst.

Today, there’s an awful lot of innovation out there. There are working business plans, as well as companies like Uber, AirBnB and Lyft that seem to be perfectly primed to march across the globe in a universal rollout of capital-backed market expansion.

But this time around, there’s something very different about the climate of investment. Silicon Valley was considered a gold mine in 1999, but the pool of people actually investing in it was relatively small.

Today, that pool is gigantic. It includes hedge funds, private equity, publicly traded corporations, and excessively wealthy eccentrics. As a result, it’s the companies that are dictating the funding, not the investors. Those companies are, in turn, spending the ridiculously large investments in real estate in downtown San Francisco, and on increasing headcount.

None of this money is coming back. And half of these firms aren’t the type of business that should require US$30 million, $50 million, or even $100 million to get off the ground.

While I firmly believe Uber and Lyft have great business models, they seem to be spending their funds on killing each other and subsidizing their drivers, rather than on simply expanding into new markets. It’s quite similar to the railroad barons of the 1800s, who would lock entire cities down in order to control the rail markets in that area. Did that help them grow their business? Sure, but over the longer haul it contributed to a less functional system of logistics for the United States.

But this is what silly money does to software businesses. The whole point of running a services-based software company is that you’re automating so much of the processes and bureaucracy of your product space that you can charge less, employ fewer people, and reliably, reproducibly profit in a semi-turnkey fashion.

Of course, turnkey never pans out that way. That’s why you hire big-brained software developers and administrators to make your services run like clockwork. But any good sys admin will tell you their primary job is to automate and make their jobs easy and low maintenance. The best sys admins do nothing until there is a problem, because it took them five minutes to get you what you needed.

Similarly with software developers, your 10x developer are worth 10 of your lesser folks. They can bang out in one day what some folks take weeks to produce.

So the real key to building a successful software and services company is finding those awesome admins and developers. Any five of each should be enough to handle a service like Uber or AirBnB, provided they’ve got a good customer support and business arm similarly equipped with top talent.

If the secret to software success is the right people, not necessarily the most people, why is everyone in the Valley staffing up, renting out $70-per-square-foot offices in downtown San Francisco, and holding giant events for customers and employees? Because they’ve got to spend that silly investment money somehow!

And that, my friends, is the soul of the bubble. When the focus of the business becomes finding ways to spend the money you’ve had handed to you, rather than finding ways to grow smartly and efficiently with a core of deeply invested individuals, you’re heading for trouble.

You can see this all around the Valley. And in my experience, it never lasts long.

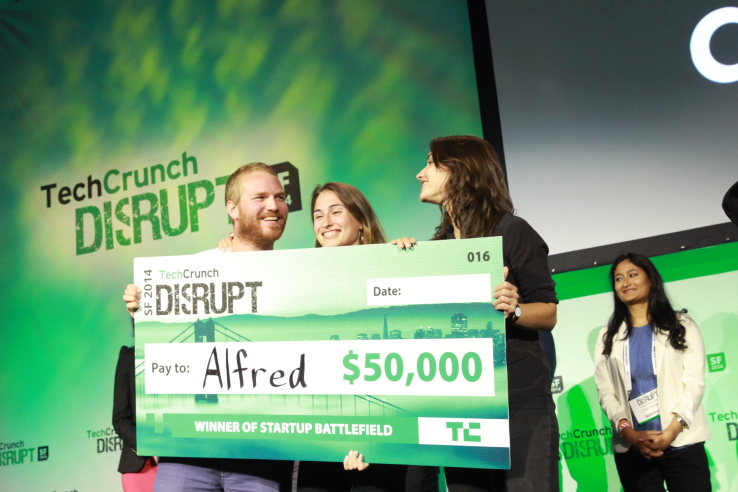

There are sure to be some super successful companies out of this recent bubble, but I can guarantee you the winner of TechCrunch’s Disrupt14 event will not be one of them. Not unless you think there’s a business in paying someone to put away your groceries.

So there it is, folks, I’m calling it now. We’re at the peak. The Valley will not remain like this forever. And when the world has crumbled, the developers will rebuild it again, as they always have.