Artists have always created using whatever medium they could get their hands on. As the tools of each technological age have advanced, art has evolved from cave drawings to oil paintings, watercolors, sculptures, photographs, animated graphics, 3D printed works and countless other media.

Today, arguably, no industry is innovating more rapidly than software development. As a result, artistic expression based in coding and programming is experiencing something of a quiet renaissance. Given the vast selection of constantly changing programs, programming languages and processes for artists to work with, no piece of artwork or artistic style is exactly the same.

Adam Ferriss

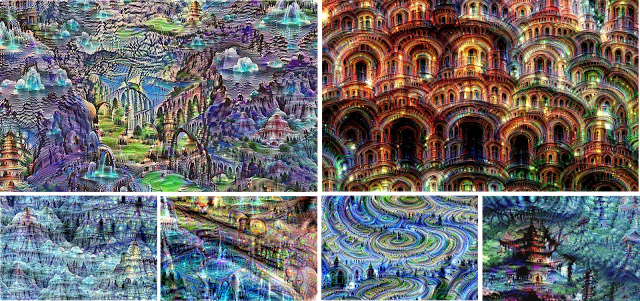

Ferriss is a Los Angeles-based photographer and artist who experiments with processes like RGB tricolor separation, pixel-sorting algorithms and shader programs to create arrays of kaleidoscopic coding art rich with vibrant color.

Ferriss was in the photography program at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, looking for ways to manipulate photographs, when a new-media class introduced him to JavaScript and basic coding. His creation method involves trying out different ways of processing, inspired by the work of other artists and driven by the curiosity to find out how they made it.

“I work a lot with noise functions, Perlin noise, or simplex noise,” Ferriss said. “They’re ways to generate pseudo-randomness in color, like shaping form. It generates a seed pixel, and from that one seed pixel it looks out at its neighbors, and continuously expands so its neighbors will start expanding. It’s essentially like you’re growing an image or a crystal in the way it clumps itself together and generatively expands.”

bitShiftMinuet from Adam Ferriss on Vimeo.

Ferriss is constantly experimenting with new programs and processes, recently transitioning from RGB separation and pixel sorting into work with shader programs—small programs that run on graphics cards. He is working with a language similar to C is but integrated into OpenGL Shader Language. It’s a hardware-accelerated way to do complex lighting and texture effects like ambient inclusion and texture mapping.

“I just got a program working that creates something called Optical Flow,” Ferriss said. “It analyzes the current frame and the previous frame for implied motion to determine in which direction the pixels are moving. Then it creates almost a motion blur, but more of a liquid flow. So if I were to have run this program on my webcam and wave my hand in front of it, I could move all the pixels in the direction my hand was moving as if they were flowing like a liquid, and they’ll scrunch and twirl and mix with each other.”

Working with coding art, where the tools and programs are still developing, gives Ferriss the chance to work with something different every day.

“You can create works and processes that have never existed before,” he said. “Learning and discovering those techniques really lets you break things down in new and exciting ways. There’s still an aesthetic to developing, but it’s also immensely satisfying to start writing a program and see that goal come to life through your code. There’s a huge sense of personal satisfaction in hitting compile and watching everything link together.”

Ferriss’ wide-ranging artwork can be found on his Tumblr and Vimeo pages.

Raven Kwok

Another artist bringing his unique vision to life through code is Raven Kwok. An animator and coder from Shanghai, China, Kwok is currently stateside getting his master’s degree in electronic arts from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Kwok’s initial academic focus was photography, but he’s since transitioned into new media art, using Processing, an open-source programming language and integrated development environment, to create mind-bending generative art pieces. His images and videos often involve geometric shapes, which animate and evolve to take on lifelike qualities.

“I design multiple ways to recursively subdivide a geometric shape, and constantly pass a continuous independent variable through the recursions to a Perlin noise function,” Kwok said. “The recursions produce parameters that follow a certain ‘wave,’ thus creating a sense of tension within the shape, which feels like being living or organic.”

F0AC from Raven Kwok on Vimeo.

In video collections like “Algorithmic Creatures” and “Fractals & Recursion,” Kwok used Processing combined with Adobe Premiere for video editing, composition and output to create an abstract, random feel. Despite the predefined audio and visual processes underneath, the randomness of the generating programs makes it so the visual elements will look different each time.

115C8 from Raven Kwok on Vimeo.

A full collection of Kwok’s videos can be found on his Vimeo page, and a gallery of his still images is open for viewing on Kwok’s Flickr photostream.

Nick Briz

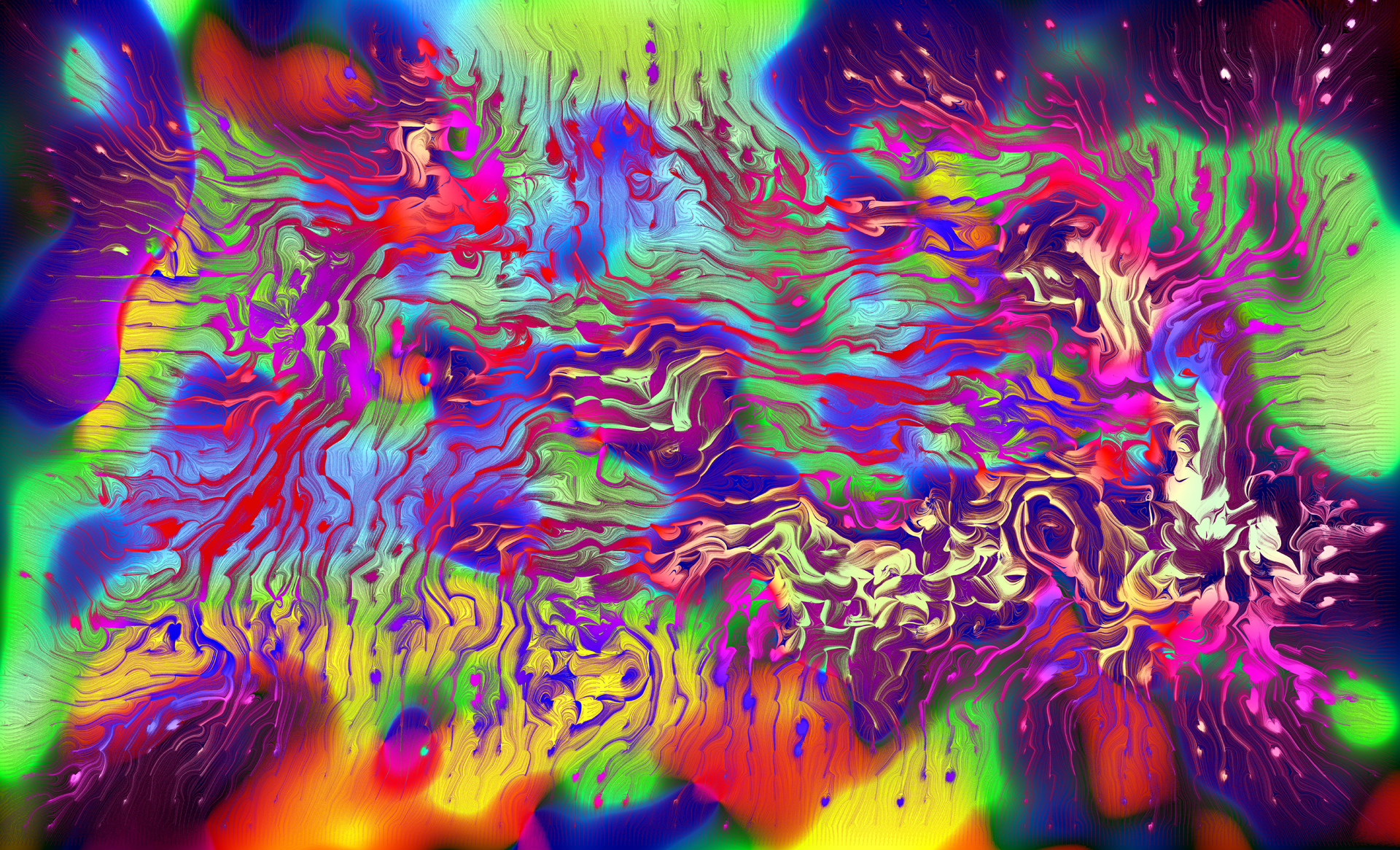

Briz, a new-media artist and digital art professor based in Chicago, is one of the pioneers of an art form known as glitch art, and he is the inspiration for some of Adam Ferriss’ work. Another artist who started as something else, Briz began as an experimental filmmaker. Inspired by the work of filmmaker Stan Brakhage, who painted directly on celluloid film, Briz began applying the same approach to digital images.

“When I started watching these Brakhage films, I thought, ‘I just can’t do that with my digital camera,’ ” Briz said. “I have no celluloid to literally paint on. I started thinking about how to distill those ideas and apply them to digital. Since Brakhage was scratching the celluloid, I figured for digital that meant just opening up the binary code of a video and hacking away at it.”

A New Ecology for the Citizen of a Digital Age from Nick Briz on Vimeo.

“Nowadays Briz utilizes a host of programs and languages to create his digital artwork, using the Sublime text editor to work with HTML, CSS, JavaScript and PHP, along with Maximus and Arduino programs. Glitch art isn’t about the programs though, Briz explained, but about the mindset.

“The glitch art ethos is wrapped in this idea of subverting the set of expectations about how we’re meant to interface with technology,” Briz said. “The whole point is to ask, how do you use this wrong? What happens when you use it wrong?”

Aside from his own work, Briz has organized efforts to spread awareness about glitch art, co-founding the GLI.TC/H festival and even creating the glitch art Wikipedia page on top of teaching digital art classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He has also combined art and academia into works like theNewAesthetic.Js, an open-source JavaScript artware library that doubles as an executable essay. “When folks get started with glitch art, one of the first things you do is Data Bending 101,” Briz said. “It’s when you take an image, and instead of opening the image up in Preview or Photoshop you open it up in a text editor, and you’ll look at is some interpretation of the binary data behind that image. You type in whatever you want and save it, then it just ends up corrupting the file and you get a glitched image.”

One project Briz recently collaborated on is called the three.js playGnd, an online tutorial, web space and open source library to bridge the gap between web developers and digital artists that teaches how to create art with WebGL. “In three.js you have this interface that’s almost like modeling 3D software. You see the code write itself as you pull sliders and toggle buttons, and learn this 1:1 relationship in real-time as you experiment,” Briz said.“In this process you have these mini-revelations, revealing aspects of the systems. The fact that you can open an image in a text editor blows a lot of students’ minds initially.”

Briz has seen the glitch art community grow steadily over the past several years since the first festival in 2010 (Briz and his co-founders are currently planning the fourth annual festival.) Each year it’s become more community-organized, with conversations and workshops on top of digital art gallery showings and the location moving from Chicago to Amsterdam and the U.K. Ultimately, Briz’s efforts to expand awareness of new media art are driven by his desire to use art as a lens to look at the world in different, critical ways. “I look at digital culture as a technology, but also as an environment,” Briz said. “I feel like I live on the Internet, so if that’s my environment, that’s what I should be creating works with. Digital artists don’t need to be poets of code, but they should be able to read poetry.”

To explore the thought-provoking artwork, ideas and philosophies of Nick Briz, visit his website.