Last year, Amazon Web Services chopped prices for the 42nd time since 2008. For many industry observers, the move sent a clear message to Amazon’s competitors that if they’re looking to scoop up some of the company’s market share, they’ll have to be willing to cut into their own profits by offering the lowest prices they can afford.

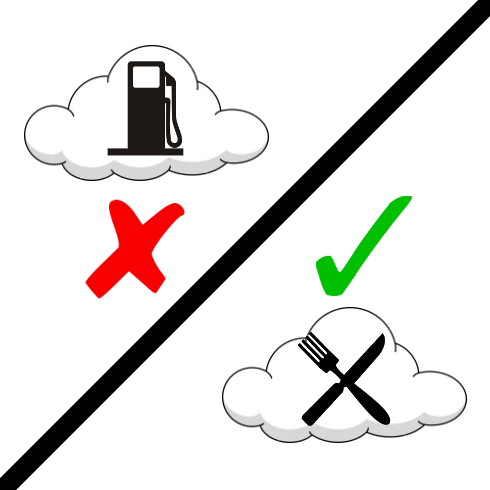

To hear these people tell it, this race to the bottom will ultimately consume the entire cloud-hosting sector. In their minds, the field is on a descent to a future of profitless prosperity, where the winners get bigger and bigger, but make less money due to falling prices. By this line of thinking, cloud hosting will ultimately become a commodity, like gasoline, where the brand name attached to the product matters little to the people buying it, and the only way to secure business is to offer an undifferentiated product at the lowest possible price.

(Related: Organization formed for developing on native clouds)

Fortunately, these people couldn’t be more wrong, and the race to the bottom is not nearly the problem some folks are making it out to be. In fact, rather than thinking of the gasoline industry, a better metaphor for the future of cloud computing would be the restaurant industry. Just as different diners choose different restaurants to satisfy different needs, so too will businesses choose hosting providers that offer the specific products and services they need to keep things running smoothly.

While some people will need a no-frills, low-price product, others will want help with legal compliance, hands-on customer service, or faster processing speeds. In the same way that you wouldn’t take a prospective client to dinner at McDonald’s, you will also want to avoid putting a valuable business partner on a no-name, bargain-bin cloud run out of a basement somewhere.

Even beyond looking for a restaurant with a certain level of quality, if your client is in the mood to eat Chinese food, you wouldn’t want to make the mistake of taking them to an Italian restaurant. By the same token, you shouldn’t steer a startup client testing a new application to the same hosting provider that you would recommend to an established enterprise needing advanced functionality like solid service-level agreements, clustering/failover, and disaster recovery.

Cloud providers are rapidly growing by tailoring their offerings to specific kinds of customers and markets, whether it is filling niches left by the big guys, to providing something radically new that you just can’t get anywhere else. Since computing is no longer something done mostly by IT departments (just try to remember the last time you bought packaged software), this means catering to the desires of the developers who now make up most of the market. These engineers will need different levels of service depending on how complex their applications are and how many people they are hoping will use them. Even within the development community, a full-stack engineer is likely to require a very different level of service or support than a back-end engineer looking to offload the front-end work to the cloud host or its integration partners.

Already we are seeing cloud companies having success targeting individual markets in the same way that restaurants and retailers do. Of course there are plenty of bare-bones providers offering ultra low-end hosting. But on the other hand, Google Compute Engine is focused on larger workloads that need scale. Amazon Web Services, the biggest player in the space, is honed in on breadth and depth. Rackspace is focusing on a service-and-support-integrated stack for customers who want a full-service product. A new nimble startup called Packet.net focuses on premium, bare-metal cloud hosting using containers.

Ultimately, the cloud space will look a lot like most other industries, where companies differentiate themselves in the market by providing different customer segments with the specialized service levels and features that satisfy their demands. The reason the industry is growing both broadly and fast is because there is tremendous demand for these varied workloads. Just as there can’t be a single restaurant to satisfy the demand for eating out, there can’t be a single cloud provider that can truly satisfy all use cases. When growth cools, there will be consolidation with multiple brands under a single umbrella. Once again, the analogy fits: Pizza Hut, KFC and Taco Bell are all owned by publicly traded Yum Brands.

Just as any good restaurateur thinks long and hard about what level of service they will provide, what will be on the menu, and what kind of person will dine at them, cloud hosting companies are at the front end of a tidal wave of demand from a customer base that is growing and demanding varied services and service levels. While restaurants have a high failure rate, the ones that get it right enjoy tremendous success. The cloud hosting industry will be no different.