When you think about a modern software monoculture, which company do you think of first? Chances are that it’s Apple. However, if I asked that question between, say, 1995 and 2007, you probably would have said Microsoft.

In agriculture, a monoculture is when too much of a region plants exactly the same crops. If there’s a disease or pest that destroys that crop, the entire region is in big trouble. Similarly, if the economics of that crop change (like a price collapse), everyone is in trouble too. That’s why diversity is often healthier and more sustainable at the macroeconomic level.

However, the problem with a monoculture is that it’s attractive. If all your neighbors are planting a certain crop and are making a fortune, you probably want to do that too. In other words, while monocultures are bad society as a whole, they’re often better for individuals—at least until something goes wrong.

Microsoft’s dominance over the past couple of decades turned into a monoculture. Vast numbers of consumers and enterprises standardized on Windows and Office, because that’s what they knew, that’s what was in stores, that’s where the applications were, and because for them personally, it seemed to be the right choice to go with the flow.

While there were alternatives, like Unix and Linux and the Macintosh, those remained niche products (especially on corporate desktops) because a monoculture rewards jumping on the bandwagon. Monocultures foster a lack of competition and a desire to play it safe. Nobody wants to upset the bandwagon. And thus, real innovation at Microsoft didn’t make it into Windows and Office, leaving room for the Macintosh to take risks, build a compelling product and start taking market share, and for Linux to tackle and win the early netbook market.

Today, Microsoft’s Windows and Office still dominate the enterprise. But even with Windows 7, I don’t think that customers are quite as willing to just do whatever Microsoft says as they used to be.

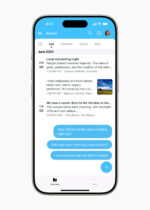

In the smartphone wars, the iPhone never became a true monoculture; there are too many BlackBerrys and other devices. However, certainly the media acts as if the iPhone is the only game in town. Apple plays into the perceptions of monoculture, offering essentially one model handset (now the iPhone 4), with the only variations being a choice of two colors and three memory configurations.

Apple’s dismissal of the well-publicized flaws in the iPhone 4’s antenna—first saying that it was a user error (you’re holding the phone wrong), and then claiming it’s a trivial software bug (displaying an incorrect signal strength)—shows incredible arrogance. And I say that as a happy iPhone 3GS owner and long-time Mac user who frequently recommends Apple products to friends and colleagues.

Any company can release a product that has a flaw. However, Apple’s behavior has been astonishingly bad. And if Apple wasn’t trying to impose a software monoculture by offering essentially one handset, it wouldn’t be a big deal. If Apple offered half-a-dozen iOS handsets, if one had a bad antenna, nobody would even notice.

The upshot, of course, is that while Apple is sure to fix the problem, we may see the early demise of the perceived iPhone monoculture. Android is coming on strong with a fast-evolving operating system and a lot of innovative work from handset makers and app developers. While I have no plans to migrate from my iPhone 3GS right now, I would definitely consider an Android device for my next purchase. Monocultures are bad, and we all benefit from a rich and diverse marketplace.

Alan Zeichick is editorial director of SD Times. Follow him on Twitter at twitter.com/zeichick. Read his blog at ztrek.blogspot.com.