It’s a whole new world for consumers when it comes to toys and devices, but with these “smart” functions and capabilities come a slew of security risks. CloudPets, a toy that brands itself as a “message that hugs,” is the latest product dominating the headlines for leaked and ransomed data that contains millions of voice recordings from kids and parents.

The CloudPets breach was disclosed via a blog post by Troy Hunt, creator of database breach disclosure website Have I been Pwned? He wrote that it was only a few weeks ago that there were headlines centered around the Internet-connected Genesis Toys doll “My Friend Cayla” over fears that hackers could use it to target children and invade their privacy. In fact, Germany banned sales of the doll because of this vulnerability. The country’s equivalent of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission alleged the toy contains a “concealed surveillance device” that violates its privacy regulations.

(Related: Software is being guarded by obsolete technology)

Then came CloudPets from Spiral Toys, which are stuffed animals that record personal messages between a parent and child. Parents can send messages using the CloudPets app, which gets approved and delivered wirelessly to the CloudPets. These audio files are stored in the cloud in a MongoDB database which, according to Hunt, “was in a publicly facing network segment without any authentication required and had been indexed by Shodan (a popular search engine for finding connected things).”

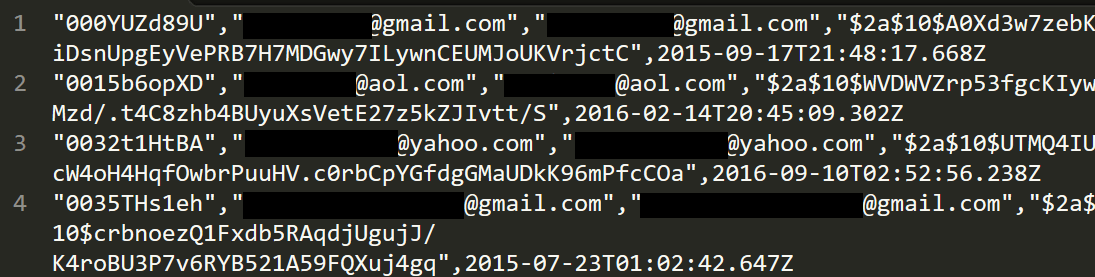

Hunt then looked into the incident and found someone who had a CloudPets account, and sure enough, there was the victim’s e-mail address in the detected breach—time-stamped on Christmas Day, the day his daughter was given the toy. Here’s what that data looked like:

The data was real, and it was determined that CloudPets left its database exposed publicly to the web “without so much as a password to protect it,” said Hunt.

From a security perspective, CEO and cofounder of Dome9 Security Zohar Alon said that these toys and devices collect information like voice messages, health data, and power consumption from their environments. This information is sent to the back-end applications, and the data is processed to generate insights, he said. The proper tools and technologies that safely store, transfer and use data already exist, such as “platforms like AWS [that] offer everything from encryption to network segmentation, to identify and access management,” he said.

“There is a risk of data being stolen at several points in the data path, from the end points and IoT devices themselves, to the back-end databases that store the data,” said Alon. “Companies building these toys should take a comprehensive end-to-end approach to security that takes into account the value of data being protected, and invest in adequate security measures to keep the data safe.”

Despite security researchers’ concerns that hackers may have access to these private voice recordings, the company Spiral Toys is denying that any customers were hacked, according to report by Michael Kan, IDG News Service U.S. correspondent.

“Were voice recordings stolen? Absolutely not,” said Mark Meyers, CEO of Spiral Toys, in Kan’s report.

According to Alon, this is not the first time an exposed, unprotected MongoDB database has been compromised and data has been stolen. He said that in the past three months, he’s heard about tens of thousands of exposed MongoDB instances being “data-jacked,” or valuable business data has been stolen or held for ransom.

Thousands of users, 2.2 million recordings, one exposed database

Mat Keep, director of product and market analysis at MongoDB, said that while there have been reports of other hacking incidents in MongoDB databases, the amount of instances that have been publicly disclosed is very small compared to the amount of downloads MongoDB sees each day.

However, Keep said that the company is concerned about any incident where MongoDB or data on MongoDB databases has been exposed. He said it’s worth noting that this incident wasn’t exposing a flaw in MongoDB. In Spiral Toys’ instance, he said the organization made a decision not to active or turn on access controls, which is provided as a standard of MongoDB databases. And when looking at the broader environment, Spiral Toys did the same exact thing on AWS S3, and set up no authentication controls there either.

“As a parent myself, it’s really scary to me that security wasn’t higher up their list of priorities as they were coming up with this application,” said Keep.

He explained that MongoDB has an “extensive array of security controls,” and access control is the top priority. But the user has to turn it on. He said it’s a bit like leaving your house; you have to remember to lock the door.

Keep added that MongoDB has tools that can actually detect if a deployment is exposed, plus they provide security documentation, security tutorials, and free security training on its website, including a security checklist so users can limit network access to just the computer where MongoDB is installed. This way, the user won’t expose themselves to the internet without taking that database off and putting it on an exposed instance.

“You can create truly mission-critical highly secure deployments, but if you choose to ignore best practices and you physically go off and expose yourself on the Internet by opening up your file—which is what happened here—any technology would be exposed or vulnerable to an attack,” said Keep.

Getting the facts straight

Both Hunt and security researcher Victor Gevers from the GDI Foundation said they discovered the exposed database from CloudPets and tried to contact the toymaker in late December. But according to Kan’s report, Spiral Toys claimed it never received the warnings.

According to Hunt, there were “many messages sent over a period of time,” and he added that VICE Motherboard information security writer Lorenzo Franceschi-Bicchierai even tried to get in touch with Spiral Toys within the last week via multiple channels. And as Franceschi-Bicchierai wrote in his story, it “could not be reached for comment.” In total, Hunt wrote that there were four attempts that they know of to warn CloudPets.

However, Kan tweeted an e-mail that Spiral Toys sent him about the data breach, which states that Franceschi-Bicchierai’s article is false. The e-mail stated that the company was informed in January that CloudPets could have been part of a massive attack that compromised more than 28,000 MongoDB instances globally. The e-mail also stated that MongoDB is a third-party provider and CloudPets does not run their own servers (Note: MongoDB is an open source database and there are several other third-party providers that offer support of MongoDB. Spiral Toys is not a customer of MongoDB, Inc.).

The company also added that “no messages or images” were compromised since they were on another server entirely, and without both the login information and password, they are nearly impossible to reach. An official statement from the company should be issued sometime this week.

Alon said that any business that is building consumer technology should have noticed that there were vulnerabilities in these toys, and they should have fixed them accordingly.

“We are reading that friendly security researchers tried to contact Spiral Toys about the security vulnerabilities but got the cold shoulder,” said Alon. “Add to that weak password policies that render password protection useless, and you see a pattern of negligent security behavior.”

Given the type of information that is recorded by CloudPets and the role that technology now plays in the lives of children, Alon said “We should treat the situation with utmost seriousness.” And since security researchers tried to contact the company in December about this data exposure, yet the problem persisted, it’s important parents think twice about trusting a company with a “poor track record like this to hold valuable data,” he said.

SD Times also tried to follow up with Spiral Toys yesterday, but hasn’t received a comment yet.