Last week, Google announced that its AI had defeated a 2 dan Go player in Europe. We covered this news, as did many outlets. The news, however, has far greater implications than many outlets let on. This is, perhaps, the largest single advancement in AI development since Marvin Minsky arrived at MIT.

Perhaps that’s why Minsky passed on last week: He knew his time was up. He released a huge amount of original AI thinking into the world. His labs at MIT were always at the forefront of the technology, frequently hooking arms and body parts up to machines to facilitate real-world AI learning challenges and human interactions.

Yet, the Minsky way of thinking is the same one that told us Go would not be defeated by a computer AI for many more decades. Some theorists put the date of Go’s defeat somewhere around 2050, a remarkably long distance from our current date, and one that would insinuate AI had as far to go as desktop computing did in 1970.

Here we are, however, at least 20 years ahead of where we should be, according to some of the smartest brains on the planet. How does defeating a top human player in Go catapult us into the future?

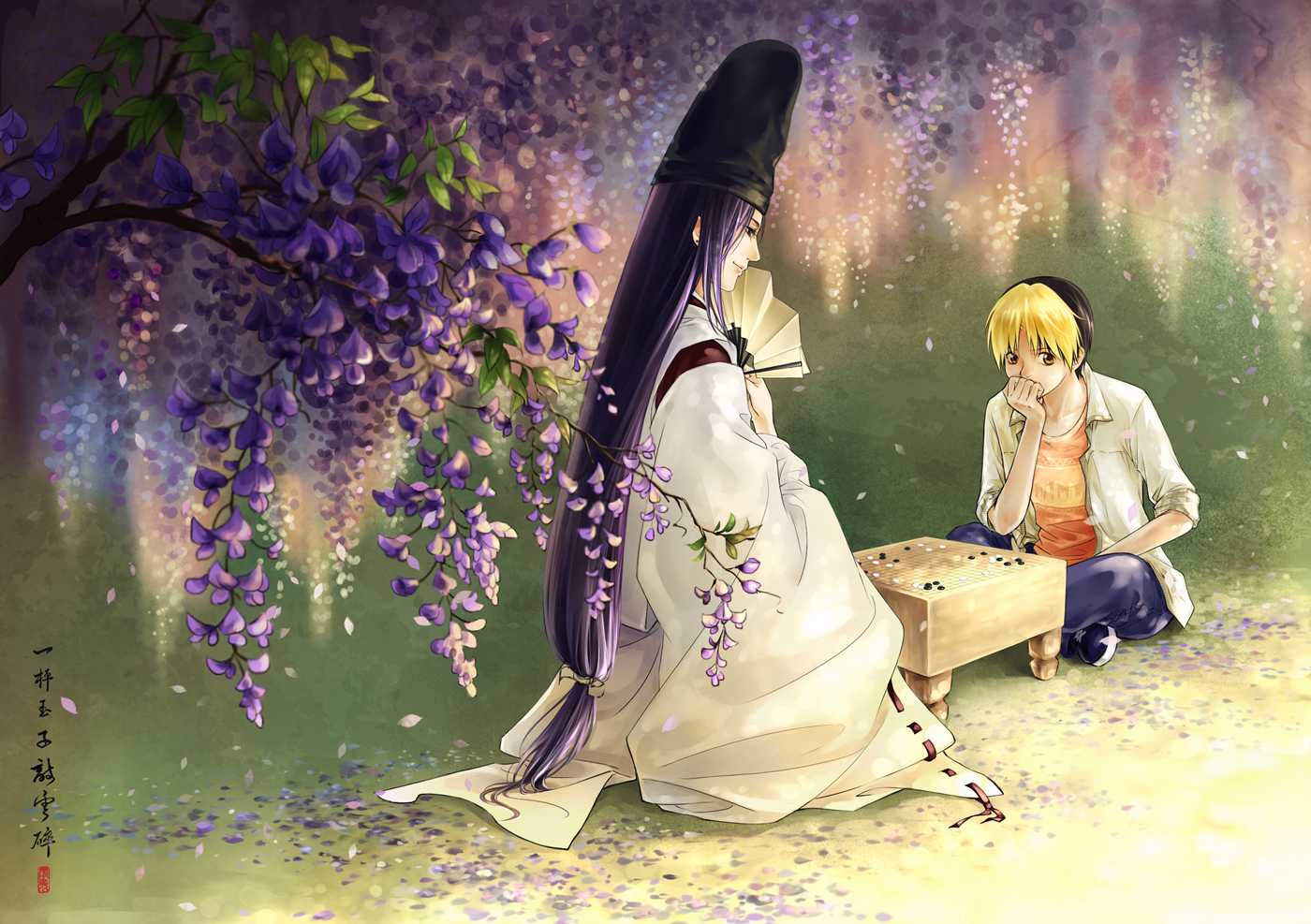

To understand why this is significant, we must first understand Go. I come from videogames, you see, and there is one truth for all good game designers out there: They all admire Go deeply and truly. This is because Go is damn near perfect, if not perfect. The rules are super simple, the board is ultra generic, and the pieces are all alike.

And yet, from this tremendous simplicity comes incredible complexity. Despite the game being well over 2,000 years old, it is said that no two Go games every played out the same. The 19×19 board is just big enough to be vast, yet small enough for a game to be over in an hour or less.

When IBM’s Deep Blue defeated Garry Kasparov in 1997, the media made a huge deal of it, saying that computers were now smarter than men. Even Kasparov felt that Deep Blue was super-intelligent, when on its 44th move in the first game, it did something nonsensical. Kasparov assumed the computer was being smarter than he could grasp, but supposedly the move was the result of a bug where Deep Blue couldn’t find a good move and picked one at random.

But let’s be fair, here: Even though Kasparov lost overall, he still had one win and three draws with Deep Blue. And let’s add to that the fact that Deep Blue was, essentially, brute-forcing the problem by calculating every possible move at every possible opportunity, and picking out the best one.

Kasparov is an amazing chess player, but a computer took him down by being able to fit a giant map of possible outcomes into RAM, and little else.

Fan Hui, on the other hand, was defeated by real, honest-to-god AI: a computer that thinks, rationalizes and predicts. DeepMind, an AI moonshot company bought out by Google in 2014, was able to predict 57% of Fan Hui’s moves before he made them. Worse yet for humans, DeepMind does not just brute-force the problem by calculating every possible move.

Frankly, brute-forcing Go has been essentially impossible for modern computing hardware. The problem space is simply too big. A 19×19 board where a stone can be placed on any empty space on any turn makes for a very large problem space, and the reason why GNU Go cannot reliably beat dan players.

Oh, I neglected to mention how Go players are ranked. I’ve been playing Go for about 10 years now. I am ranked (and I am guessing here because kyu ranks are self-applied) 29 or 28 kyu, with 30 kyu being the worst possible Go player. After 1 kyu comes 10 dan, which runs down to 1 dan, which is the best possible player rank. There is a single 1 dan player in each major region: Korea, Japan, China, and “the West.” Fan Hui was 2 dan in Europe, meaning he was the second best player there.

As second best, he could only be defeated by the best. Now, it’s time to find out who is the best of the best: humans or DeepMind.

The dan rankings are so succinct and ancient, they have a few transitive properties. The first such involves time: Go players, throughout history, can be ranked against one another because the kyu/dan system dates back to the 17th century. The Chinese ranking system, involving pins, dates back as far as the second century AD.

The other major property of the dan system is that it caps at 7 for the amateurs: 6 dan and higher can only be attained by professional Go players.

In absolutely no universe, no parallel dimension, no alternate universe, could a 6 dan ever beat even a 2 or 3 dan, let alone a 1 dan. In fact, when you start getting to the lower dans, even a 2 dan playing against a 3 dan could require a handicap of 2 or 3 stones played freely with no response.

So, here we have a system where the difference in skill level, even between the immensely talented, can be as large as the gulf between pro and amateur. We have a game that is far older than almost every nation on Earth, and we have a computer program which is now, at least in theory, as good as the best Go players in the world.

AI enthusiasts have called Go a bellwether for this very reason. Many fans of the Singularity (the concept that we’re just counting down the days until we create a sentient computer being) have taken this defeat of Go as a sign that it is far closer than we’ve thought.

Other, more down-to-Earth AI folks have taken this as a sign that algorithms can, in fact, take on some of the more generalized problems we’ve kept from them. Go is not just a game that can be defeated with a logic map; it’s a game that requires intuition.

You must use intuition to determine what play will be made next. There are very few instances in Go where you’ve got an obvious best move. But there are far more times in the game where it’d be smarter to start laying stones on the complete other side of the board rather than just go for the throat in contested territory.

From an AI standpoint, DeepMind seems to be using intuition. It has to make judgment calls based on things other than rote numbers and probability. It has to build a map of the opponent’s moves and patterns in its RAM.

DeepMind was thinking very specifically about what its opponent was doing. It played according to the opponent’s skills and patterns. Deep Blue, on the other hand, would have played the exact same way against me as it would have versus Kasparov: by looking things up in a big table.

DeepMind, on the other hand, was thinking. It was reasoning. It was beating a human at its own games. A game without arbitrary movement rules. A game without overpowered queens that can stomp other pieces. A game almost as old as civilization itself.

The singularity may be closer than we think. Deep Mind beat Hui five games to zero. No draws. Humanity lost, soundly. There are only two or three 1 dan players in the world on which to now test Deep Mind. One of those players is largely not considered to be as good as the others, simply because he is western and not Chinese, Korean or Japanese.

But soon all Go players won’t be considered to be terribly good: not when we have a 0 dan computer in the house.