Four years ago, the Beijing Olympics opened with an awe-inspiring spectacle that included a gigantic scroll powered by human voxels, fireworks that “walked” toward the stadium, and 2008 synchronized drummers. It was reputed to have cost more than US$100 million, and director Zhang Yimou praised the ability of the Chinese to produce “performances [that] are totally uniform, and uniformity in this way brings beauty.” It was, to draw a software parallel, as perfectly executed as an A-List videogame: a Halo or a Call of Duty, with every pixel accounted for and pushed to its limits. How, everyone thought, could London compete with that?

Danny Boyle’s opening to the London Olympics showed exactly what to do when you want to impress but are limited to dramatically fewer resources: Don’t compete at all, but rather respond in a way that makes a virtue of scarcity and non-uniformity. Where Zhang presented a pixel-perfect montage of Chinese achievements, Boyle tossed out an intensely quirky set of touchstones: the predictable pastoral idyll and Branagh-delivered Shakespearean quote gave way not to, say, Elizabethan culture or Newtonian science or sunset-proof cultural and political dominance, but rather to Victorian smokestacks that the vapid TV hosts informed us actually smelled of sulfur. Some soldiers in World War I outfits made an appearance, but the Blitz and Battle of Britain had to be put aside for dancing nurses, creepy inflatable babies surviving Voldemort and Captain Hook, and Sir Tim Berners-Lee inventing house music. (Did you notice that he was working on a real NeXT cube?)

The whole thing reminded me of Monty Python’s “Confuse-A-Cat” sketch, in which a cat is stuck in a rut (“Suburban fin-de-siècle, ennui, angst, Weltschmerz, call it what you will.” “Moping.” “Hmm, I must remember that.”) Only by exposure to absurdist Dadaist nonsense can the cat, Olympic viewer, or intimidated software developer be reinvigorated.

I loved it. Boyle demonstrated a tactic that should be remembered by every startup: Don’t let your better-funded rivals define the competitive ground. If you’re an independent game developer, don’t let Mass Effect 3 dictate your graphics, and if you’re developing your first mobile app, don’t judge success by seeing if you’ve knocked the latest iteration of Angry Birds off the leaderboards.

This doesn’t mean that you can be sloppy or do a half-hearted job and expect to be rewarded because you’re less well funded or newer to the marketplace. If you’re going to have the Queen jump out of a helicopter, she’d darn well better have the Union Jack on her chute and it better open without a hitch (I wonder if HRH packed her own?). If you’re going to ship an indie game with deliberately blocky graphics, you’d better have great gameplay. Your line-of-business app doesn’t need custom animated transitions, but if you use CSS round corners on some pages, you have to use them on all your pages.

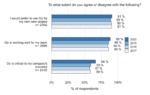

But it does mean that you should consider whether to use basic animated transitions or CSS round corners on any page. Why not create an in-house application that uses Plain Old Links and hypermedia to model application state? Sure, at this point an application that consists of Headings, Unordered Lists, Tables and Plain Old Links is going to appear quirky. On the other hand, users understand the Web, developers understand the Web, it’s easy to change labels and help text, and performance has a shot at being noticeably crisper. Importantly, by being aggressively Spartan about the interface, developers and clients can focus on delivering value, the “what” and “why” and not the “how.”

If you travel the “quirky and individualistic” route, though, it’s important that you maintain architectural discipline and don’t lock yourself into an initial concept. Interfaces that are overly coupled to domain logic and application assumptions are the rule rather than the exception, even though experienced developers and managers know how limiting it is to be locked into a flawed user interface. And of course, if your dramatically personal user experience doesn’t resonate, the failure will settle heavily on your shoulders. But no one makes it to the Olympics without risking failure.

Larry O’Brien is a technology consultant, analyst and writer. Read his blog at www.knowing.net.