If you live in anywhere in the U.S., perhaps this weekend you may have noticed herds of people wandering the streets, staring at their phones and searching for something. Those somethings were Pokémon, and those people were trying to catch ‘em all. Even if you don’t like video games, this is a watershed moment for mobile applications, and you need to be paying attention.

First, find the person in your office who is playing. There’re likely a few, and they’re likely around 30-something. Find your nearest players and sit them down. Make them explain the game to you and how it works. I’ll do so here, but there are nuances, and seeing it in action will be helpful.

(Related: Augumenta introduces an augmented reality interface)

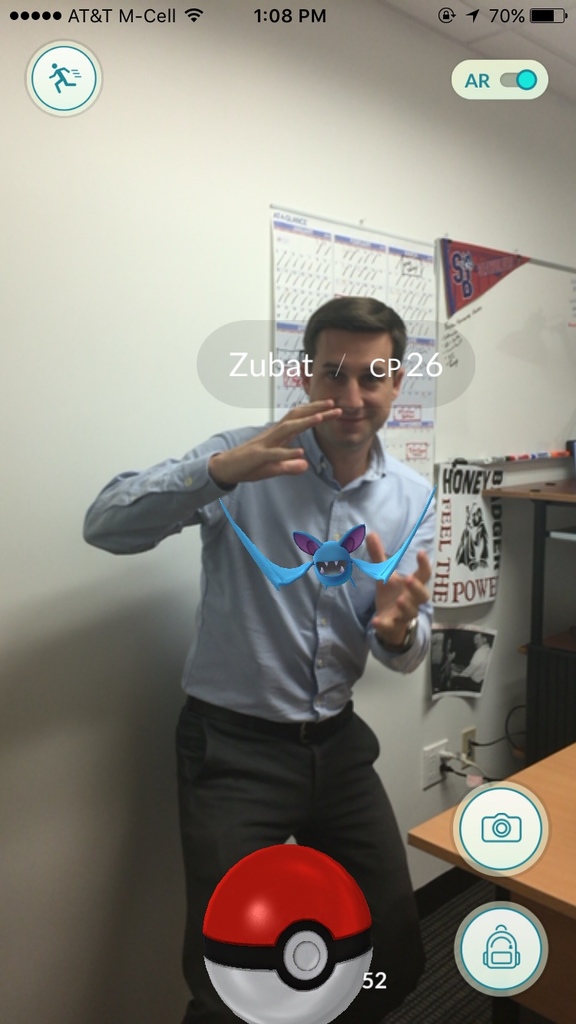

My basic explanation is as follows: Players wander around in the real world with the game client open, and as they near hidden Pokémon in the world around them, they can capture them and add them to their collection. Pokémon appear in the real world where they would in nature: Water Pokémon appear near rivers and lakes, ghost Pokémon appear near churches and graveyards, grass and bug types appear in parks, and so on.

Immediately, you’re asking, “How does it know where these things are in the real world?” Because Pokémon Go is by Niantic, the Google company behind Ingress, a similar game launched about four years ago.

Ingress was, essentially, the same game minus the hidden Pokémon. Players wander the real world and use their experience points to “hack” other teams’ nodes. Each node is a dot on the map put there by players over the course of the game.

Thus, Pokémon Go launched with not only Google Maps’ intrinsic geolocation knowledge, it launched with the original Ingress database of locations, meaning there were not only locations all over downtown Manhattan, but also in Peoria, Anaheim, and even small-town USA.

That’s a nationwide rollout of thousands of geolocations, all previously vetted. What does that mean? That means none of the locations are deep into private property, or on military bases, or in restricted areas. None of them will make you walk off a cliff, or get you into the path of a landing airplane.

That’s HUGE. The four years prior to this launch must have been heavily dedicated to building a safe list of geolocations. It is almost unimaginable the trouble players could get into if geolocations for the game were near nuclear waste dumps, classified installations, or just old man Jeb’s backyard.

Just take a moment to digest the magnitude of this task for Niantic, and the importance of this type of testing and vetting for future apps like this.

Another extremely important aspect of Pokémon Go you should be paying attention to is Lures. Lures are used to bring Pokémon to an in-game Pokéstop (geolocation). Because Lures last for 30 minutes, there’s an incentive to hang around one for a while.

That’s the nitty-gritty in-game strategy stuff, right? Well, kind of. It’s also the single most important in-game purchase a business can make. Why? Because for US$1, you can literally increase foot traffic to your business for 30 minutes by putting a Lure on the nearest Pokéstop.

The comic book shop near my house did this all weekend. People were piled up outside the door grabbing Pokémon, chatting, and sharing tips. Pokémon show up about once every five or six minutes, so it gives you time to hang around and socialize.

Process that for a moment: Using a virtual item in a virtual world overlaid with our own, a retail establishment can now drive real-life foot traffic to their business using a virtual in-game item to improve the experience for all who play nearby.

You can physically see the way this game is affecting the world. Gyms are the game’s focal point for between-player conflict. There’s a gym near Lake Merritt in Oakland that is basically just a tree in a park with no real benches or meeting spaces. Still, Sunday afternoon, a dozen teenagers were there, at the tree, hanging out and defending the gym.

Learn about this game. Play it if for no other reason than to understand it. You can see how it works under the cover by playing. For example, thanks to numerous app crashes and restarts, I now know that the wild Pokémon around me are being transmitted from the server in a sort of message queue, with older ones dropping off the queue but remaining in the client’s memory for a bit longer. These Pokémon are in-world persistent too, which means you can tell other players where they can find specific Pokémon. When you catch one in a specific place, for the next 20 or so minutes, others can catch it there too.

I’m already pushing for an in-depth tech interview, but it would seem Niantic is a touch busy at the moment. Pokémon Go in four days gathered more downloads than Tinder, and has more active users than Twitter.

This is the new norm for a killer app in our society, and this is the new norm for augmented reality. Go play the game, then push back your mobile apps launch date until you can digest the lessons learned from Pokémon Go.