After discovering malicious users that were using open-source projects to participate in dangerous activities like bitcoin mining, SourceClear created a free project to help the community discover suspicious builds before they become an issue.

SourceClear, which is dedicated to helping developers use open-source software safely, has spent the last 18 months trying to dig deep into the problems of the open-source world. As a result, SourceClear discovered a bunch of issues that weren’t immediately on the organization’s road map, but it scared them enough to do something about it, according to founder and CEO of SourceClear, Mark Curphey.

He said that when developers build someone else’s open-source code, they place all of their trust into them, which is normally fine since most developers are upstanding citizens and are developing open-source projects for the good of the community, he said.

(Related: Looking into the future of software security)

After some research, Curphey said they started noticing plenty of malicious activity. Some of this activity included bitcoin mining with open-source projects, where every time a developer would build their project, an instance of a Continuous Integration server would begin mining.

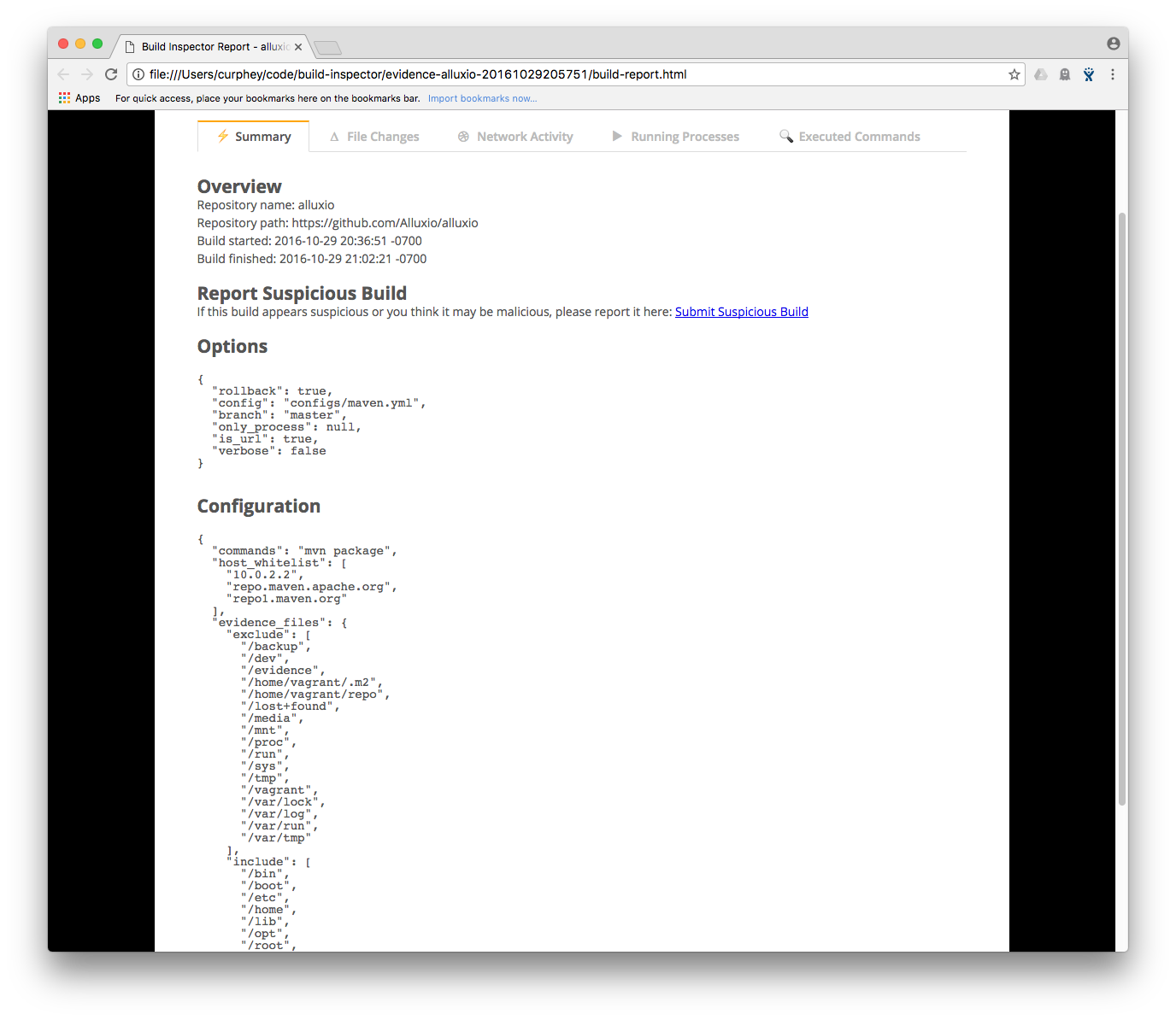

To combat these exploits, SourceClear created Build Inspector, an open-source forensic sandbox for Continuous Integration environments. Build Inspector can watch network traffic, file changes, and watch processes and threads to make sure no one is creating a backdoor or modifying files after the build happens.

Using the sandboxed environments, build operations will occur in isolation, so there can be no compromising of the machine, said the company. Requirements for Build Inspector include Ruby (2.2.3 is recommended), Vagrant and Bundler. Once those are installed, the developer can add the Sahara Vagrant plug-in and bundle install the project’s dependencies.

“Eventually, this technology will get based into our technology, but in the interim we wanted to do the right thing and help the open-source community protect themselves and be safe,” said Curphey.

The reality, according to him, is ransomware is moving up from the desktop into enterprise apps. SourceClear has been observing other cases where people have been packaging bad libraries and pushing them out to the open-source ecosystem. These malicious trends are similar to what happened with viruses, which took off because instead of targeting one person’s desktop, a person could target an entire server and impact a whole team.

“You can target one person and a hundred thousand people run [the software], and it’s much more effective for the attacker,” said Curphey. “What we are seeing is the economics of the bad guys really has shifted with reusable code.”

Running untrusted code can open up several dangerous scenarios for today’s developer, said Curphey. For instance, a person can trick a developer into thinking he or she is using 10 different types of open-source libraries, but underneath the hood those libraries are being pulled from a malware hosting site.

Another possible scenario is a developer pulling an open-source library that is “perfectly fine,” but a malicious user can replace the library with one that is bad, said Curphey.

According to Curphey, Build Inspector is not something developers would want to put into production because it spawns a virtual machine and slows down the build process. Developers can use Build Inspector if they are suspicious of something in their open-source code or libraries, and this way, they can run it through the sandbox to figure out what’s going on before the developer uses it for an enterprise application, he added.

“Open-source is fantastic and continues to be,” said Curphey. “The problem is you have to know what open source you have. The second thing is you have to know where it came from. The third thing you’ve got to know is what it does, and the fourth thing is does it contain any vulnerabilities.”