To name a few, or rather most, Arial, Helvetica, Times New Roman and Verdana are the Web fonts most readily available to Web designers and developers today. One initiative to end this limited selection is the pending standardization of the Web Open Font Format by the World Wide Web Consortium standards body.

Called WOFF for short, the new file format is intended to help enable the use of high-quality typography for the Web, and to address browser compatibility issues. At the moment, “Firefox supports the file format and Internet Explorer 9 will,” said Steve Lee, product manager at font foundry Monotype Imaging. He also said Google will implement WOFF in the next Chrome release, and he expects Safari to jump on board once WOFF becomes a standard.

Until this initiative, “Web authors could only use fonts that are available locally on users’ computers,” explained Vladimir Levantovsky, W3C WebFonts Working Group chair and senior technical strategist at Monotype Imaging.

“With WOFF, any font can be used to create a Web page because the same font will be delivered to a browser whenever the Web page is accessed. This means that authors will now have full control over text appearance, page layout, language selection, etc.,” he added. “Anything and everything that depends on a specific font choice will now work the same way.”

For senior Web designers like Samantha Warren at Web publisher Phase2, this is a real evolution. It’s backwards how fonts are now, she said, referring to how some browsers can only read certain fonts. “But this will certainly cut down development time and reduce technical implications. It’s now one file format and call it a day.”

However, for font foundries, “Font is now part of the recipe,” Lee said. “Our vision is much wider now,” because fonts mainly used for print purposes will need to be serviced for Web integration, he said.

For high-quality computer monitor displays, fonts will also need to be reworked to about 72 dots per inch, Lee said, while a laser printer, for example, can print 600 DPI.

But outweighing this one con is the pro of recurring revenue, Lee said. “This is a profound change in our business model. Instead of selling perpetual licenses and ‘losing’ a customer, we will now sell the fonts as a service.”

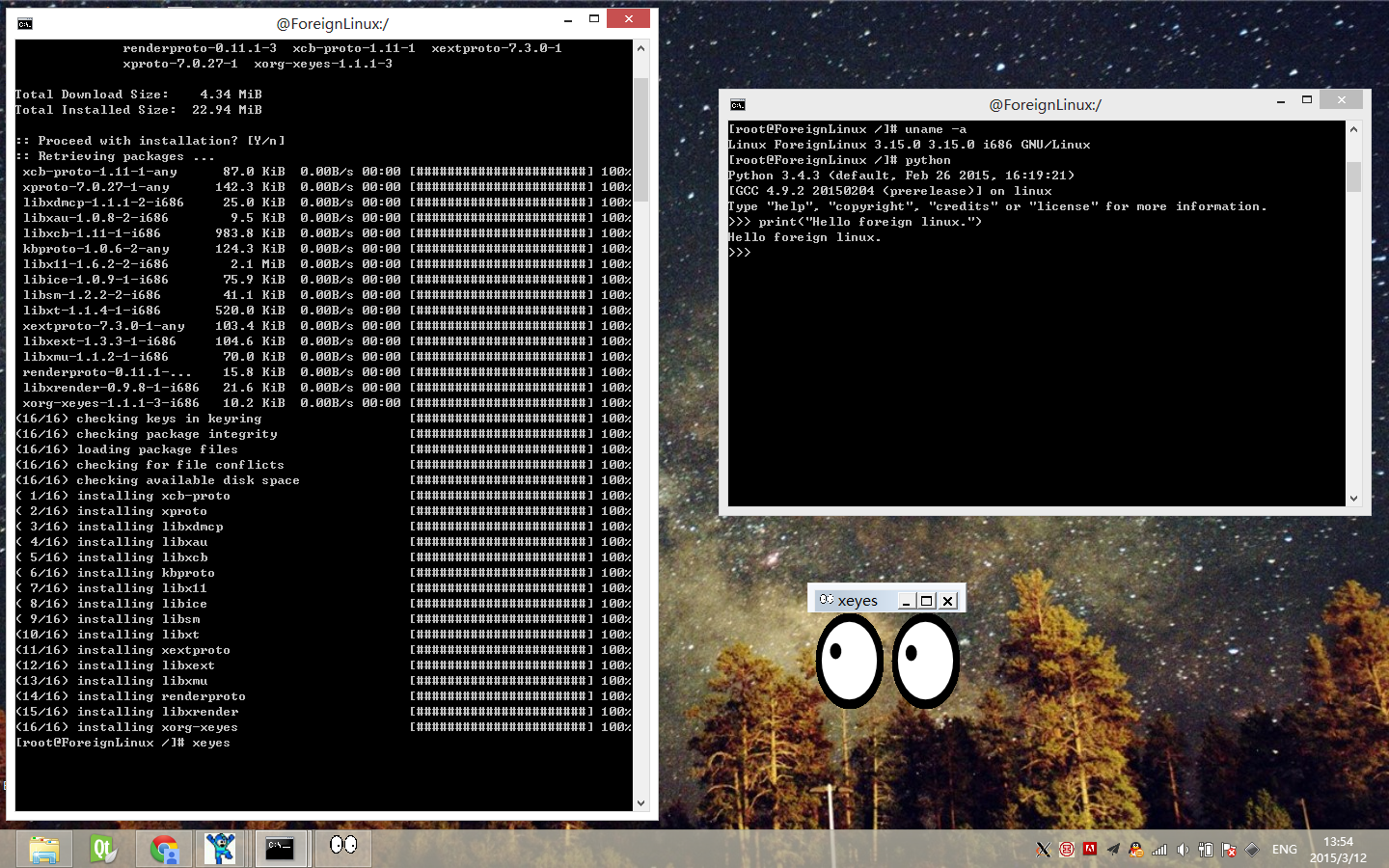

Another avenue for access to more fonts is the Google Font API. Introduced in late July, users can choose a font, and the API will generate the corresponding code to be copied and pasted into their Web pages. However, “This is just a way to use fonts and is not related to the [browser] format,” Lee said.

Aside from more font options, another added bonus with WOFF is “text remains text,” Levantovsky said.

A common workaround for text display today is to render it as an image, so a human can see the text on the screen, he said. “The negative of text content presented as an image makes it non-searchable. As far as a browser is concerned, it’s an image.”

Levantovsky said that real text can also be turned into speech for sight-impaired users, providing more accessibility to the Web.

Still in draft form, WOFF is expected to become a standard within a year.

“I’m just really interested in seeing the Web move forward,” said Warren, “and I’m happy that some common ground has been found.”