As fun as they are, videogames are still just software at their core. And that’s why this year’s Game Developers Conference in San Francisco was not just a place to play around. Enterprise-focused companies like ARM, Basho, Couchbase and Intel were all on-hand to discuss their software with the developers who make videogames for a living.

While attendees learned about the PlayStation 4 and the latest mobile graphics processors, software development companies were also making the rounds. Francisco Monteverde, CEO of Codice Software, was touring the show to demonstrate Plastic SCM, the distributed version-control system his company created.

Montverde said that Git has shown developers the usefulness of a distributed development model, but some of the classic Git problems are still causing woes. One of those problems is the 2GB limit on repository sizes, a major issue for game developers who also like to store their art assets in company software repositories.

Plastic SCM, said Monteverde, is not limited to a 2GB repository size, making it a compelling alternative to Git for game developers. And another problem for many Git users is the platform’s confusing new take on merging. He said that Plastic SCM offers a simple and fast graphical tool for performing merges, and for viewing the timeline of changes and merges in a project.

That’s not to say that Plastic SCM doesn’t work with Git. As GDC opened on March 25, Codice announced a new tool that allows this SCM system to integrate with Git repositories.

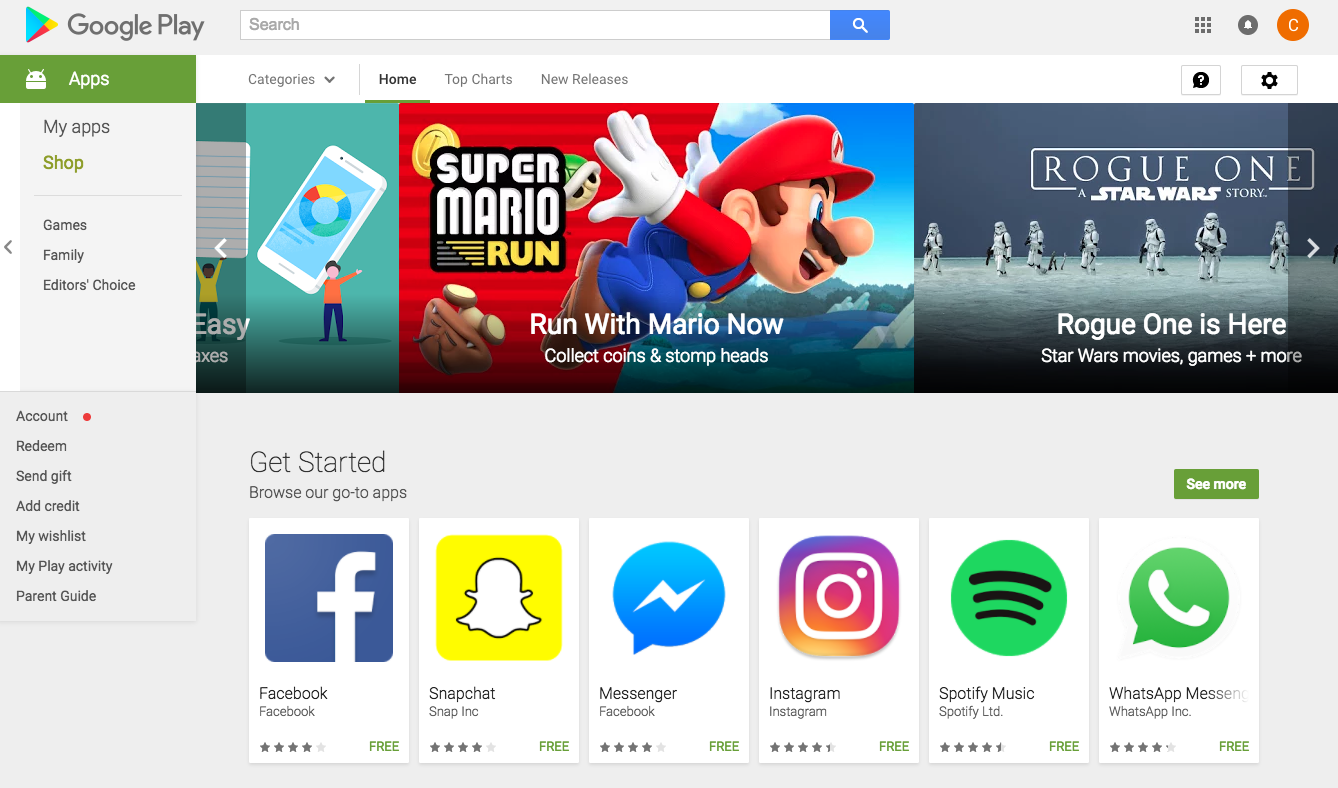

Also at GDC were a handful of mobile application analytics and management platforms. From Swrve to Fuse Powered to Flurry, mobile application management was a hot new topic for developers. This is unsurprising, as games in mobile app stores are extremely competitive. These mobile analytics solutions allowed developers to control and monitor their already-deployed mobile applications, as well as to track user retention and monetization.

#!

The ARM angle

Of course, all those mobile devices are powered by ARM processors. ARM Holdings, the company that licenses ARM technologies, was at GDC to exhibit some of its software-development and testing tools.

Anand Patel, product manager for Mali tools at ARM’s Media Processing Division, showed off updated and new graphics-troubleshooting tools for the Mali graphics processor, ARM’s mobile graphics chip.

ARM’s Mali profiling tool hasn’t changed much since last year, but the company did add support for OpenCL to it. Patel also demonstrated a graphical debugger, which the firm hopes to have available in beta form by summer.

The new graphics debugger allows developers to step through a scene frame by frame, and to observe the contents of the framebuffer as each element is drawn into memory. As a result, significant errors in polygon overlap—even inefficiency—can be detected, said Patel.

“We’ve seen many instances where an entire room has been drawn in the background, and we draw something on top of it, so that’s wasted cycles. This helps identify this types of issue,” he said.

Innovative ideas

Outside of software-development tools, the conference was packed with new products. From NVIDIA’s forthcoming handheld game console, the SHIELD, to the mysterious VR goggles known as the Oculus Rift, game developers are awash in new hardware, software and platforms.

Platforms like Sifteo, a small touch-screen device that can be linked together to form a grid of multiple little screens. Or the Ouya, a Kickstarter-funded Android-based videogame console that looks to be on the market later this year.

And therein lies the biggest change for the videogame market in the last year: Kickstarter. This crowdsourced funding platform has revolutionized the game industry almost overnight. Numerous classic gaming franchises have had reboots funded through it in the last 12 months, including Carmageddon, Wasteland, Shadowrun, Elite, Broken Sword, and even Leisure Suit Larry.

This fundamentally turns the videogame industry upside down. The classic publishing model for it has been similar to that of movies or music: A development studio receives a large advance against royalties from a publisher, then garners whatever meager funds remain after the advance is paid back, the marketing is paid for, the distribution is covered, and so on.

And like the music industry, many content creators were frustrated with the publisher model, which removed control and stability from what have become extremely large development teams. Like what happened in the music industry, many developers would come out of a publishing deal no longer owning their own intellectual property and deeply in debt.

Game development studio InXile’s founder, Brian Fargo, recently kickstarted his career in videogames back to life. Fargo was the founder of legendary but long-dead game company Interplay. When Interplay effectively dissolved around the turn of the millennium, Fargo created InXile, but had little success getting the company funded or moving toward any finished project.

That all changed when Fargo discovered Kickstarter. After successfully using it to raise US$2.9 million to create Wasteland 2, Fargo’s virtually unknown gaming company went from a stalled also-ran to the hottest company in the industry almost instantly.

But that was nothing compared to Fargo’s next trick: raising $1.9 million for his next project, a Planescape: Torment reboot called Torment: Tides of Numenera, in less than six hours (and it’s still taking donations).

Indeed, over $100 million has been raised on Kickstarter for videogame projects alone. For an industry that has long been beholden to the Nintendos, Electronic Arts and Activisions of the world, Kickstarter represents a real alternative to the publisher model of software distribution, and has brought many long lost and much loved classic game franchises back to life.