Imagine you are building a house. You get all your tools, lay out the lumber, and start constructing the first room. As you are building the room, you decide if it’s a living room, or a kitchen, or a bathroom. When you finish the first room you start on the second, again deciding, as you build, what kind of room it will be.

Let’s face it, no one would do that. A rational person would first figure out what the house should look like, the number of rooms it needs to contain, how the rooms are connected, etc. When the plans for the house are complete, then the correct amount of supplies can be delivered, the tools taken out, and construction begun. Architects work with paper and pen to plan the house, then, and only then, carpenters work with tools and lumber to build it. Everyone associated with home building knows that you figure out what is wanted before determining how to build it.

RELATED CONTENT:

The most uninteresting reason your project might fail

5 tasks project managers must perform to ‘sell’ their proposals

Arguably, the fundamental principle of systems development (FPSD) is also to figure out what the system is supposed to do before determining how to do it. What does the user want? What does the system have to do? What should system output look like? When the what is understood, then the how can start. How will the system do it? How should the system generate needed output? The how is the way users get what they want.

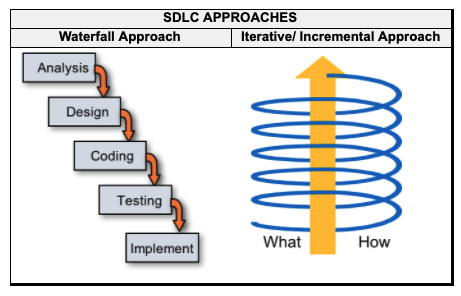

The IT industry has long recognized that confusing the what with the how is a major cause of project failure resulting in user dissatisfaction from poor or absent functionality, cost overruns, and/or missed schedules. Ensuring that the what is completely understood before attempting the how is so important that it was engraved into the dominant system development life cycle methodology (SDLC) of the time—the waterfall approach.

For those of you who just recently moved out of your cave, the waterfall SDLC consists of a series of sequential phases. Each phase is only executed once, at the completion of the previous phase. A simple waterfall approach might consist of five phases: analysis, design, coding, testing, and installation.

![]()

In this approach, the analysis phase is completed before the design phase starts. The same is true for the other phases as well.

The good news is that with the waterfall approach, systems developers did not have to remember to put the what before the how because their SDLC took care of it for them.

Then iterative and/or incremental (I-I) development came along and, the rest, as they say, got a little dicey.

Although there are dozens of I-I approaches, they are all variations of the same theme: make systems development a series of small iterative steps, each of which focuses on a small portion of the overall what and an equally small portion of the how. In each step, create just a small incremental part of the system to see how well it works. Vendors like to depict I-I development as a spiral rather than a waterfall, showing the iterative and incremental nature of these approaches.

Using an I-I approach such as prototyping, a session might consist of a developer sitting down with a user at a computer. The user tells the developer what is needed, and the developer codes a simple solution on the spot. The user can then react to the prototype, expanding and correcting it where necessary, until it is acceptable.

This is obviously a very different way to develop systems than the waterfall approach. What might not be so obvious is that the various I-I methodologies and techniques, such as rapid application development, prototyping, continuous improvement, joint application development, Agile development, and so on, still involve figuring out what is wanted before determining how to do it.

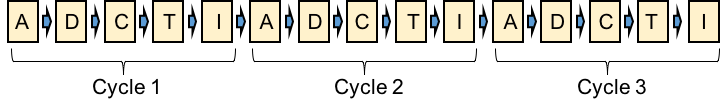

Rather than looking at I-I as a picturesque spiral, an I-I approach can be viewed as a string (or vector for you programming buffs) of waterfall phases where each cycle consists of a sequence of mini-analysis, mini-design, etc. phases. However, rather than each phase taking six months they could be no longer than six weeks, or six days, or six hours.

It might take a half-dozen cycles of sitting down with a user to figure out the requirements (the what) and then coding the results (the how) before showing them to the user for additional information or changes, but the principle is always the same—understand the what before determining the how.

However, too many developers throw out the baby with the bathwater. In rejecting the waterfall approach, they mistakenly ignore the basic what before the how—the FPSD. The result is the reappearance of that pre-waterfall problem of project failure resulting in user dissatisfaction from poor or absent functionality, cost overruns, and/or missed schedules.

Why? How could something so well understood as ‘put the what before how’ be so ignored? Here are three common reasons for this troublesome behavior.

Reason 1. Impatience (Excited to Get Started)—Many in IT (the author included) started their careers as programmers. Programming is a common entry-level position in many system development organizations. It is understandable that new (and not so new) project team members are anxious to start coding right away. In their haste, FPSD is not so much ignored as short-changed—corners cut, important (sometimes annoying) users not interviewed, schedules compressed, etc. The result is an incomplete understanding of exactly what the users want.

Reason 2. Not Understanding the Value of Analysis—Analysis, or whatever your call it (requirements, logical design, system definition, etc.) is the process of learning from users their requirements (the what) and then documenting that information as input to system design (the how). However, analysis has endured some heavy criticism over the past few decades. Some feel that it is overly laborious, time consuming, error prone, or just not needed at all. The result can be an incomplete understanding of what the new system needs to do.

Reason 3. Confusion about the FPSD and the Waterfall Approach—The waterfall SDLC is viewed by many as a relic of IT’s past, offering little for today’s developers (not entirely true, the waterfall approach still has its uses, but that is a subject for another time). Unfortunately, the what-how distinction is closely tied to this approach so any rejection of the waterfall approach contributes to skepticism regarding any what-how talk.

What’s a project manager to do? How do you ensure the what is understood before the how is undertaken? There are three things the project manager can do.

Training—The problem with most systems development rules and guidelines is that the reason they should be followed is not always obvious. Or has been forgotten. Systems developers tend to be an independent and skeptical bunch. If it was easy to get them do to something, then documentation would be robust and project managers would earn half what they do now because their hardest job would have disappeared. No, managing a team of developers is like teaching an ethics class in Congress—difficult, underappreciated, and often exhausting. The one saving grace is that systems developers like to create great systems. The vast majority of developers take great pride in doing a good job. The project manager needs to tap in to that enthusiasm.

The easiest way to get systems developers to do something (other than forbidding them from doing it) is to convince them that doing it is in their and the project’s interest and that separating the what from the how is in that category.

But wait. You can hear the challenge right now. “We are using Agile development, so we don’t need to separate the what from the how.”

The answer is that the purpose of the what-how distinction is not to create separate development phases but is to make developers think before they act—to ensure that before the design hits the page or a line of code is entered on a screen, the problem is mulled over in those high-priced heads.

Is this approach counter to Agile development or any iterative-incremental approach? No. Read the books and vendor manuals more closely. There is not one author or vendor who believes you can skip the thinking if you use their tool or technique. The problem is that many of them are not sufficiently vocal about the value of thinking before acting.

Discipline—The problem is usually not knowing (most know to complete the what before starting the how), the problem is doing. A good way to get team members to do the right thing is to codify the desired behavior before the project kicks off. Rules, standards, and strong suggestions presented before a project starts are more likely to be accepted and followed by team members than mid-project changes, which can be seen as criticisms of team member behavior.

The project manager needs to lay out the project rules of engagement, including such things as the SDLC method or approach to follow, the techniques and tools to use, documentation to produce, etc., all focused on ensuring the what is completely understood before starting the how.

Then comes the hardest part of the entire project—enforcement. The project manager needs to ensure that the rules of engagement are followed. Failure to enforce project rules can undercut the project manager’s credibility and authority. A few public executions early in the project do wonders for maintaining that project manager mystique.

Collaboration—Want to influence a systems developer? Need to convince developers to follow systems development best practices? Then have him or her collaboratively meet with other systems developers. The team walk-through is a great vehicle for this.

In a team walk-through the developer presents, demonstrates, and defends his or her work, not to users, but to other team members. The developer walks the other team member through the user requests, his or her analysis of those requests, their solution to the request, and finally any demonstrable work products. This friendly IT environment is a useful way to test if the developer’s work is thorough, efficient, and complete.

This is should be a slam-dunk. Team walk-throughs can be very motivational, inspiring (shaming) underperforming developers into producing better results while providing overachievers an opportunity to show off. In both cases, the user, the project, and the project manager win.

George Tillmann is a retired programmer, analyst, systems and programming manager, and CIO. This article is adapted from his book Project Management Scholia: Recognizing and Avoiding Project Management’s Biggest Mistakes (Stockbridge Press, 2019). He can be reached at georgetillmann@gmx.com.