In 10 years, Michael Torres wants to be the CEO of a gaming company. He sees himself founding the next EA or Ubisoft.

“I’m interested in creating software and developing games,” Torres said. “I’ve always wanted to do that since I was a little kid. I was always playing Lego Star Wars when I was little and I really enjoyed it, so I thought, why not try to get a job doing this?”

But that will have to wait for now. At the moment, Torres is a ninth grader at the Academy for Software Engineering in Manhattan, and his favorite class is a tie between integrated algebra and gym. He’s one of 250 students enrolled at the AFSE, a new high school dedicated to the design and development of software. The academy is now in its second year, offering both a ninth- and tenth-grade class, each totaling about 125 students.

Inside the classroom

The AFSE (and its sister school BASE, the Bronx Academy for Software Engineering) are the first steps in New York’s fast-developing pipeline fostering the next generation of software and technology professionals who, city officials hope, will power economic growth in the city behind a new wave of technological innovation.

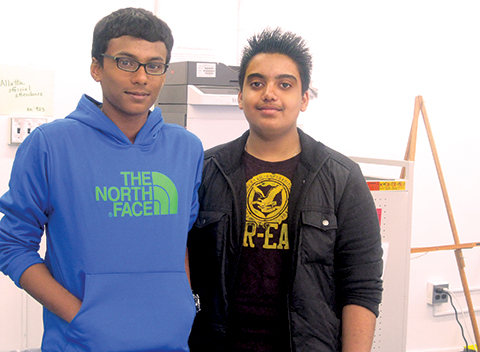

Michael Torres with classmate Erlyn Ysit

Over a planned four years at the AFSE, students will move through a curriculum of computer science courses combined with typical classes like English, history and math. Even standard classes are integrated with CS-based tools and skills, though. For an assignment on “To Kill a Mockingbird” or the War of 1812, students might create a Web page or Scratch project (using a tile-based visual programming toolkit) instead of handing in a paper or a PowerPoint presentation.

The AFSE has unscreened enrollment, meaning admission decisions aren’t based on academic performance. All students need to do is attend an open house, apply, and hope their lottery number is picked.

The school’s two computer science teachers come from eclectic backgrounds: one a former Amazon and Microsoft software engineer, and the other a former classical guitar maker. And the AFSE is actively recruiting more specialized teachers as the school expands. Classes right now range from robotics and Web design to Advanced Placement computer science, as well as programming classes delving into languages like Java, Python and Ruby.

(More on educating the next generation of developers: Doubling the talent pool)

Outside the classroom, the AFSE immerses students even more deeply in the world of software engineering. Field trips take students inside the New York offices of companies like Facebook and Google, and the school matches each student up with a professional mentor on top of summer internships. It’s a natural progression from there to college, and in the New York area alone the school has close ties to Columbia, NYU and Pace University.

The school’s philosophy—more than simply giving kids a leg up on the latest software knowledge or industry trends—is based on equipping students with the skills, concepts and experience to flourish no matter what technological change the future brings.

“We’re taking an entire school and acculturating them in software engineering and computer science,” said Leigh Ann DeLyser, the AFSE’s computer science consultant. She works with computer science teachers to develop curricula, and with non-CS teachers to integrate computer science into their classes, along with cultivating professional connections and partnerships with the school. “The students who walk our halls are the next generation of creators. And whether that creation happens in software engineering or in some other field, the skills they learn here will just help them fuel that creative spirit as they move forward,” she said.

Building out an idea

The AFSE occupies the fourth floor and half of the fifth floor of the Washington Irving High School, right by Union Square. The school is scheduled for closure by 2015 due to low graduation rates, but in its place the AFSE and four other academies are gradually expanding within the building. They’ve made made this modest chunk of the aging building their own, hanging inspirational slogans, plaques with tech billionaires’ bios, and the histories of programming languages on the walls. Not to mention installing two brand new computer labs and branding each room with a different software company logo.

Down one fifth-floor hallway, the Samsung room faces the Pinterest room, which is next to the Facebook room and across from the Microsoft and Vine rooms. A student came up with the renaming idea last year.

The Academy grew out of a shared idea. Back in the late 2000s, Mike Zemansky, then and still a computer science teacher at Stuyvesant High School, and venture capitalist Fred Wilson imagined a school where computer science was a core, fundamental subject. They proposed the idea to the New York City Department of Education, and Wilson—a managing partner of Union Square Ventures with investments in companies like Foursquare, Disqus and Twitter—offered to help fund it. Originally envisioned as a school where the city’s best and brightest were screened for admission, the AFSE became a place where any New York City student with an interest in software engineering or app development could apply.

Washington Irving High School, home of the Academy for Software Engineering

“In our first year, we were a brand new school,” DeLyser said. “They told us we’d be doing awesome if we filled our seats, and we’d be doing phenomenal if we got 300 applications.” The AFSE received more than 800 applications to fill 120 seats for the 2012-2013 school year, and this past year it received 1,500 applications. “Our expectation this year is that we may double that again,” she said.

The history of ‘Silicon Alley’

The term “Silicon Alley” can be traced back to the mid 1990s, used to describe Internet and new-media companies clustered in the Flatiron, SoHo and Tribeca areas of Manhattan. It eventually becomes a general term for the tech industry in New York City.

The term really began to take hold in 1995-1996, when newly launched publications like @NY, AlleyCat News, Silicon Alley Reporter, and the greater New York media began covering the emerging venture capital and tech opportunities in the area. The name was popularized, and the idea of New York City as a center for technological innovation on the East Coast was pushed.

After the dot-com bubble burst, “Silicon Alley” began making a comeback with the help of events like NY Tech Meetup and nextNY, connecting tech professionals in the city and encouraging more startups. Now with Mayor Bloomberg’s recent economic and educational push, a term that’s been thrown around for almost two decades may finally hold some real meaning.

Changing educational culture

Politicians often preach that America needs more STEM education—science, technology, engineering and mathematics. But according to DeLyser, the United States is overproducing in every category of STEM except technology.

“We only produce about a third of the computer scientists we need in this country for the jobs we have,” she said. “If we filled every open computer science or software engineering job in the United States with an American, we’d be at 4% unemployment right now, as a nation.”

DeLyser, who went back to school after 10 years of teaching to do educational research and learn how to train computer science teachers, wrote a paper in 2010 entitled “Running on Empty: The Failure to teach K-12 Computer Science in the Digital Age.” She echoed one of her main points through an unusual metaphor.

“CS education in the United States is like a glass of champagne. There are lots of tiny little bubbles, and those bubbles keep rising to the top, and you keep seeing them, but by no means are the bubbles coming together to fill the glass with air,” DeLyser said. “And so CS education was all of these little tiny bubbles of excellence that made things happen, but there was still a lot more liquid in the glass than air.”

DeLyser pointed to a 2009 study by the Computer Science Teachers Association showing declining availability and enrollment in CS and Advanced Placement computer science classes. Of the 1,100 participating high school computer science teachers, only 27% reported that their schools offered AP computer science, compared to 40% in 2005. According to the study, only 74% of schools offered any computer science courses, compared to 85% in 2007. The culture of computer science and software engineering education, she said, was in need of sweeping change.

The still relatively new AFSE welcomed the BASE this fall, with an inaugural ninth-grade class of 115 students. DeLyser and AFSE principal Yu have kept an active dialogue going with BASE, and the two schools are looking at planning a meet-and-greet or Google Hangout between students.

The computer science teachers from each school have also begun to co-plan, weighing in on each other’s curricula. (There is no set New York City Department of Education curriculum for the schools to follow.)

But the AFSE and BASE are far from the only New York City schools integrating CS and software engineering classes. According to DeLyser, an additional 28 schools are offering computer science classes this fall that didn’t have them before. Ten high schools and 10 middle schools are offering classes through Mayor Bloomberg’s new Software Engineering Pilot Program, run by the New York City Department of Education’s Office of Postsecondary Readiness, while other schools utilize a program called Technology Education and Literacy in Schools (TEALS), a national grassroots organization that pairs software engineering professionals with teachers.

“The software engineer comes first period in the morning to co-teach a class, so that you don’t have to have a teacher who has all of that knowledge, and they receive a lot of support training from the TEALS organization,” DeLyser said. “So there’s a lot of this growing in the city outside of just our little school.”

Yu also mentioned the Pathways in Technology Early College High School in Brooklyn, where he worked under that school’s principal before the AFSE hired him. He explained that “P-Tech” runs under a different model from grades nine to 14, where graduates walk away not only with a high school diploma but also an associate’s degree.

This hybrid school has become something of a media darling, referenced in speeches by U.S. President Barack Obama and New York State Governor Andrew M. Cuomo. Yu was quick to point out though that the AFSE, opened in 2012, is the first high school in the city specifically focused on software engineering.

“Every school is definitely going to meld their own formula,” Yu said. “But I think for us, because we’re the first school to do this and be specifically focused on computer science and software engineering, we’d love to be a hub and really try to impart some of the things we’ve done well and things we’ve learned. I do think if we want CS to really grow across the city and within schools, then having a number of schools closely interact would be extremely beneficial.”

Tailoring personalized pathways

“Many of our students come in with little to no background in computer science, so we start with a level playing field,” said DeLyser. “We teach them basics of computer programming, Web design and some other really fundamental things in the first year. Our goals for Year 1 are not to turn out software developers.

“We have them for four years. We want to give them a foundation that supports their confidence in themselves, because we all know software engineering is a lot about solving problems. They’re not the kind of problems where you can raise your hand and have the answer right away. You have to struggle with the problem a little, and that takes self-confidence.”

(Another software education initiative: Bringing ‘Free Libre’ software to schools)

The students’ freshman year is what the AFSE labels their “Toolbox Course.” Students get a mix of technologies, taking intro to computer science and elective courses like robotics and Web design. In computer science teacher Sean Stern’s introductory class, his ninth-graders are in the midst of constructing their first robots before getting a taste of programming.

“Today I’m getting all the groups caught up on their robots, and the follow-up to that is beginning programming with them,” said Stern. “Our math teacher designed that curriculum so it ties in with a little bit of algebra—like, how long do you have to power the wheel to make it go a certain distance—and you can imagine mapping that to a linear function, and sort of connecting that within the mathematics curriculum.”

Stern is a former software engineer who spent more than a year working on retail systems at Amazon, using Hadoop to analyze shipment costs. Before that, he spent more than two years at Microsoft working on the Windows 8 app store.

He found his way to the AFSE through a nonprofit organization called Girls Who Code, which tries to close the gender gap in technology and engineering fields through programs and classes for high-school girls. He was volunteering as a teacher and speaker when he met DeLyser, who also serves as curriculum coordinator for Girls Who Code.

Stern left Amazon in 2012, and spent much of last year student-teaching while getting his certification. He started as a full-time computer science teacher this fall, and runs the school’s Mac lab.

“Most people don’t have a good understanding of what software engineers do or what computer scientists do,” Stern said. “There’s computer science you can do without a physical machine, that it’s not the same as building a computer. I think the habits of thinking associated with that field are very powerful, like how to break down problems into step-by-step pieces, how to test them, how to iterate on things. I guess I like sharing that, and offering the knowledge to high-school students when there’s a sore need for that kind of availability.”

The students enrolling at AFSE come in with different skill sets, so the coursework must be relevant to each of them.

“We’ve tried to develop a curriculum where they feel like computer science or software engineering is something they can do,” said Stern. “Our assignments are such that if every kid comes in here and follows the basic instructions, they have the capability to produce something they find interesting. We also have kids who say, ‘I’ve done Python before,’ so we try to put meaningful challenges in our projects so those kids aren’t disengaged.”

Stern loves using Scratch, a tile-based visual programming toolkit, in his intro to computer science class. Even building something as simple as an About Me project allows the students to create something in the mindset of a software developer: to build, test and improve something. The AFSE is focused on teaching concepts and skills more than keeping up with the constantly evolving software industry.

“I think sometimes people get too caught up in how to integrate with what the industry is doing today, because if I was learning this stuff in high school, it would’ve been like, ‘Java! Everything in Java!’ ” said Stern.

“I mean Android is in Java, and it’s a valuable skill to have, but think about now with Ruby, jQuery, all those other languages. It’s more the tools to learn that stuff that we care about more than cloud computing or Big Data per se. They’re important insofar as they teach concepts, not that they’re used by the industry.”

(What’s going on with Java: Building Java; rebuilding the JCP)

DeLyser added that the goal of the school is to base academic performance less on grades and more on what students accomplish and create.

“A lot of the work that we do is around the building and construction of artifacts in all of their classes, and ways that their academic performance can be based upon the things that they produce and the skills they demonstrate,” she said. “We really want to give students more opportunities to build things that exist outside of the classroom. Projects and things we can engage with them that will live on their cellphones, that will be public on the Web, which will be used not just for a grade in a grade book.”

Armed with a set of skills and the right mindset, students move down the personalized pathway into year two, the A.P. year. Some sophomores take A.P. Computer Science, essentially an introduction to programming in Java. Other students are part of the College Board’s pilot program for the new A.P. Computer Science Principles course. Students can choose between the two based on their level of interest in programming, with A.P. Compute Science course being more rigorous.

After these first two years, the personalized pathways will really start to take effect. The school plans to negotiate for more building space each year, expanding into more of the fifth and part of the sixth floor of Washington Irving to accommodate two more 125-student classes. Juniors and seniors will have a better idea of what areas of computer science they want to explore, with a menu of electives to choose from. These electives also vary depending on the expertise of the teachers the AFSE hires. If a teacher comes in with experience in robotics, or graphic design or app development, they’ll offer advanced courses in those subjects.

“After the first two years, which are pretty well set for the students, they now have a good understanding of what the field looks like,” DeLyser said. “They know what a software engineer is; they know who a tech support person is. They have this vision of what these careers might mean. So then they’re better able to select the elective courses that will meet their own personal goals.

“So some of our students may decide that a four-year college program is not for them; that computer science is maybe too rigorous a discipline for them. So instead we’re providing them with hardware support courses, as an example. We’re looking at multiple pathways for multiple types of students.”

New York’s pipeline to Silicon Alley

Ameer Baksh and Pomeroy Mohabir are best friends. They’re both 10th-graders at the AFSE, and the school set them up with internships at Morgan Stanley last summer.

They want to go to college together to somewhere like MIT or Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University: Baksh for mechanical engineering and Mohabir for aerospace engineering. A decade from now, they want to start an aerospace company together, designing fighter jets and spacecraft for the coming age of space travel, along with the software to pilot and control them.

Pomeroy Mohabir (left) and Ameer Baksh plan on working on their own aerospace company after college

Baksh and Mohabir are just two of the students moving through the pipeline from schools like the AFSE through internships, college and directly into the workforce. If soon-to-be ex-Mayor Michael Bloomberg has his way, Baksh and Mohabir would base their aerospace startup in New York City’s “Silicon Alley” rather than San Francisco’s Silicon Valley.

The AFSE’s ability to create internship opportunities and professional connections for students is founded in the relationships the school has already fostered with New York-based software companies, and the AFSE works with them on three levels. The lightest commitment on the companies’ part is through an iMentor program, where individual professionals volunteer to mentor AFSE students, e-mailing back and forth once a week and meeting up once a month.

On the second level of the school’s professional network are speakers and field trips. Many of the companies send one or more employees—often toting company merchandise—to the AFSE to give assemblies, or even employees from human resources departments to do mock interviews with the students.

The third and arguably most important level gives students software engineering internship opportunities they normally wouldn’t pursue until college. Last summer, 12 students (including Baksh and Mohabir) did six-week internships at Morgan Stanley, with several others interning at JPMorgan Chase. They all worked on real projects that the companies have implemented into their systems.

“I worked for this team in [Morgan Stanley’s] Information Security Department,” Mohabir said. “We make rules for people to follow so they won’t launder any money. So I made a website for them, used HTML…and it turned out pretty professionally; they loved it. It’s a good thing this school taught me HTML.”

In two years, when the inaugural AFSE class looks toward graduation with these internships on their résumés, the school sets them up on a clear path to college. The AFSE’s college advisory board has members from Columbia and NYU to help students network, and while nothing is stopping kids like Baksh and Mohabir from going to MIT, Bloomberg would prefer they stay local.

Bloomberg has pushed hard to make New York City a college destination for computer science majors, with Cornell NYC Tech and its planned Roosevelt Island campus the result. Cornell won Bloomberg’s yearlong contest to fund an applied sciences school in 2011, though for now the NYC Tech campus consists of a third-floor loft in Chelsea occupying space donated by Google. The Roosevelt Island campus is planned for a 2017 opening, but its construction won’t be completed until 2037.

In the same way Bloomberg’s economic incentives have enticed software and technology companies to open Manhattan offices, these high school and college expansions are all part of the foundation on which Silicon Alley will be built.

“Mayor Bloomberg has been so supportive because he sees that the lack of pipeline is an economic issue,” DeLyser said. “Silicon Valley has this shiny glow around it, right? That’s where you want to go as a CS major when you’re done and you want to do something cool.

“What we’re hoping to do here in New York is create a cadre of people with professional training and experience who have a loyalty to the city. It’s where they grew up; it’s where their families are. So we’re feeding the pipeline not only with people who’ll have the skill set we need, but who also see New York City as home, and will hopefully continue to stay here after they graduate from college.”

Innovating computer science education across the U.S.

While New York’s strides in CS education may outpace others, it’s far from the only place in America where programs and school districts are bolstering the “T” in STEM education.

One of the earliest examples of CS education reform began in the Los Angeles Unified School District back in 2004, with an organization called the Computer Science Equity Alliance (CSEA). Its efforts to expand high school access and broaden participation in computer science more than doubled the number of A.P. CS courses offered in LAUSD from 11 to 24, and drastically increased the number of female and minority students enrolled in the classes.

Out of the CSEA has grown the Exploring Computer Science (ECS) curriculum, which has expanded to statewide education initiatives in Oregon and Utah, as well as the Washington, D.C., Santa Clara and Chicago school districts. The yearlong curriculum is broken up into six topics: human-computer interaction, problem solving, Web design, programming, computing and data analysis, and robotics. In Chicago in particular, every high school now offers an optional ECS course.

DeLyser said the AFSE is aligning its ninth-grade curriculum with ECS goals and standards in an effort to partner with Chicago schools. “We want to bring our teachers from New York City into that community of practice, so they can share lesson plans, and participate in activities and things like that as well,” she said.

Another initiative DeLyser mentioned is an organization called the Computer Science Teachers Association (CSTA), for which she used to serve on the board of directors. The CSTA has chapters in almost every state and support from universities around the U.S., and its members total more than 15,000 worldwide in countries like Canada, Israel, New Zealand and the U.K. The CSTA connects and supports CS teachers around the world, developing a community of CS educators to share ideas, compare curriculums and teaching strategies, and spearhead programs and initiatives.

The next generation of innovators

Erlyn Ysit wants to be a software engineer at Google. Right now, she’s a ninth-grader at the AFSE, and her favorite class so far is robotics.

“I love robotics. I’ve never done it before; it’s really fun,” Ysit said. “We’re making this robot that basically picks up a box, that’s it. But there’s so much work behind it.”

(Perhaps Erlyn will work on the Tacocopter: A dream for all drones)

“Ten years from now, these students are going to be some of the most sought-after graduates, because they’ll have this history of experience, and also this real connection to New York City and its community,” DeLyser said. “I think it’s just going to make them some of the most attractive new hires as they come out of college and into the New York City tech workforce.”

What’s happening with computer science education in New York City is unprecedented. Students like Baksh, Mohabir, Torres and Ysit are receiving wide-ranging classroom experience and professional exposure to the world of software engineering and application development. High schools, colleges, software companies, and an entire city are partnering in pursuit of a common goal—creating opportunities for a diverse young generation to pursue the careers of the future, with Silicon Alley jobs waiting for them.

“One of the really exciting things about our schools is that we’re ethnically representative of New York City public schools,” DeLyser said. “We are 96% minority or bi-racial, and these students see the world differently than the majority of the current software engineers. They come from different backgrounds, different heritages.

“Using that knowledge and life experience, they can build more diverse things and attract a larger population of consumers, just because they come from that world and they have different perspectives. We all know that a diverse team makes more diverse products, and I think diversity is going to be their biggest contribution to tech innovation.”