The saying “opposites attract” is true for programmer Daniel Holden and poet Chris Kerr, the creators of Code Poetry, a collection of 12 code poems that produce a visual representation of a poem when they run.

At a glance, Code Poetry (written as ./code –poetry) appears to be a collection of random animations and lines of code. Holden and Kerr realized the project can be difficult to “wrap your head around” (as Kerr put it), but from their perspective, that’s part of the visual arts process. As much as coding is functional and makes things operate, it also can be something abstract and a way to get people to rethink about what it means to make art.

Holden and Kerr are two high school friends from southwest London, and while they grew up in the same area, their college careers set them out on different paths. Holden attended Edinburgh University studying graphics and animation, while Kerr attended Cambridge University for English literature. Although Kerr is a published poet, he said he has worked with software companies in the past as a technical writer, so he has had indirect exposure to code.

The project began after Holden entered a competition called Source Code Poetry, which was inspired by the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare. While he enjoyed the competition, he wanted to start his own project to create poetry that would be more compelling and interesting to read. Now, their site contains 12 of those poems, with a print and e-book available that have five new poems that do not appear on the site.

In the beginning, Kerr would write the poems first before Holden wrote the code, but they quickly learned that it was better to go from the code to the poetry and then meet in the middle, said Kerr.

“My initial instinct was to just write poetry, but it was more useful to actually talk to [Holden] and learn more about how the language worked, and it fit more naturally,” said Kerr.

When they first started, Kerr would send Holden his original poems, who would try to turn them into a program that would run an animation. But, Holden found that he was changing so much of the poem, it ended up altering the feeling or meaning behind Kerr’s poem, said Holden.

“So then, I would write a basic program and send it to [Kerr], and he would replace variables and insert different words in different places,” he said. “Then we would go back and forth a few times to refine it.”

Each of the 12 poems is written in a different programming language. Holden said most of the projects on the site produce some sort of animation, which means he had to write programs that produced a program while still displaying a poem inside of the code.

Unlike the original competition Holden entered, he wanted to have each of the programs stand next to the poem and the code that belongs to it. Each poem has its own theme or subject, and some have different-colored syntax highlighting to make some of lines stand out.

“Something that really struck me was just how different in character the programming languages are, and when you are not a developer and you don’t know much about code, it seems like such a monolithic thing,” said Kerr. “We set out to kind of visually and artistically capture the individual character of, say, Perl or Ruby, so it could be appreciated at first glance by people that do not know coding.”

Holden said he had some fun working in so many languages, but part of the challenge was trying to make the code as small or as simple as possible. The code that produces the animation needed to be hidden somehow inside each poem, while still allowing it to run as intended.

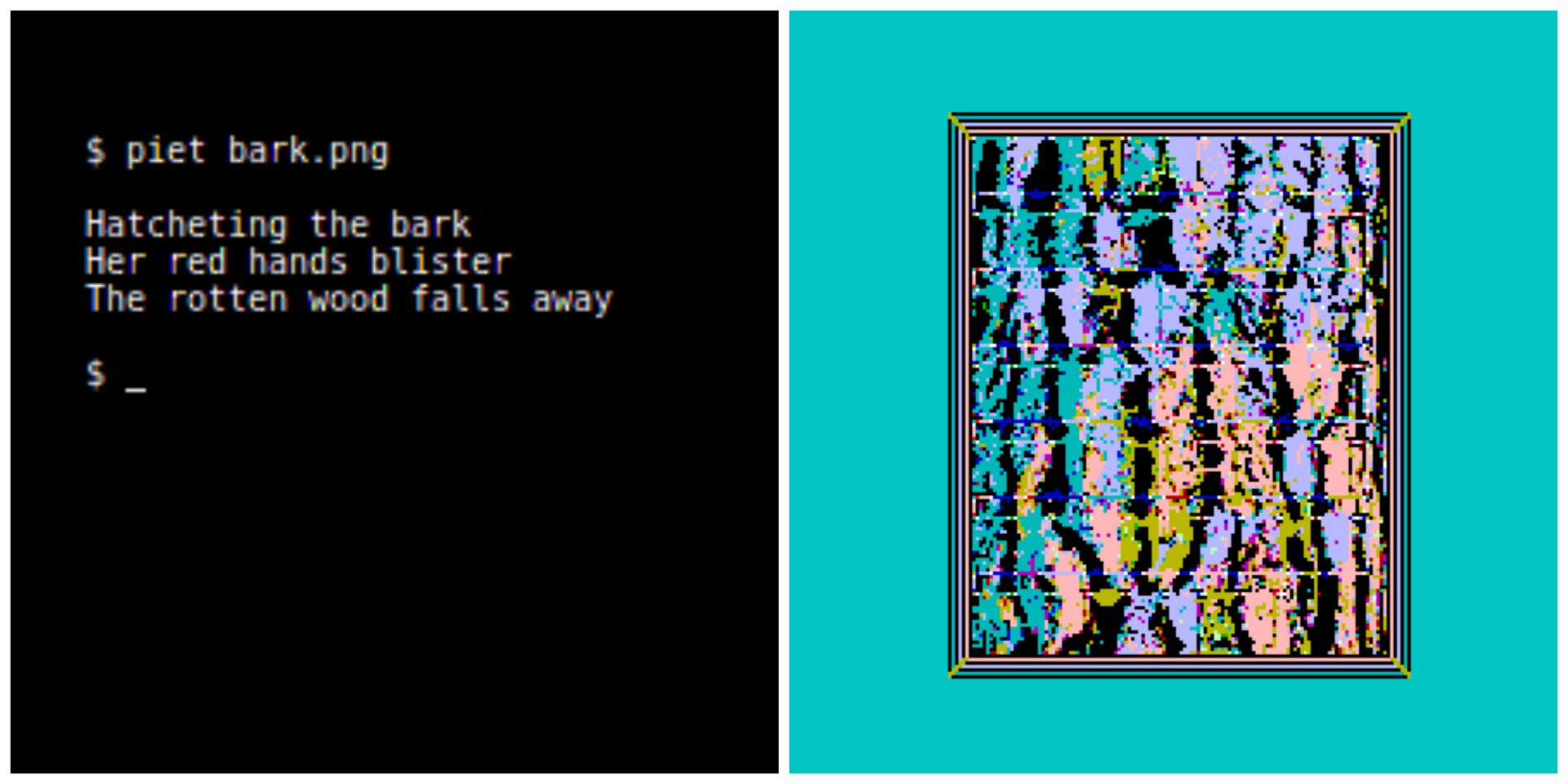

A weird, esoteric programming language called Piet was one of the more interesting languages to work with, according to Holden. Piet takes input like a picture instead of source code, and then it interprets the pixels in the picture as the code. The program, called “Bark,” is hidden in a picture that is meant to portray tree bark.

When the program runs, it produces a haiku poem on the left, giving viewers a different experience than some of the other ones on the site, said Holden.

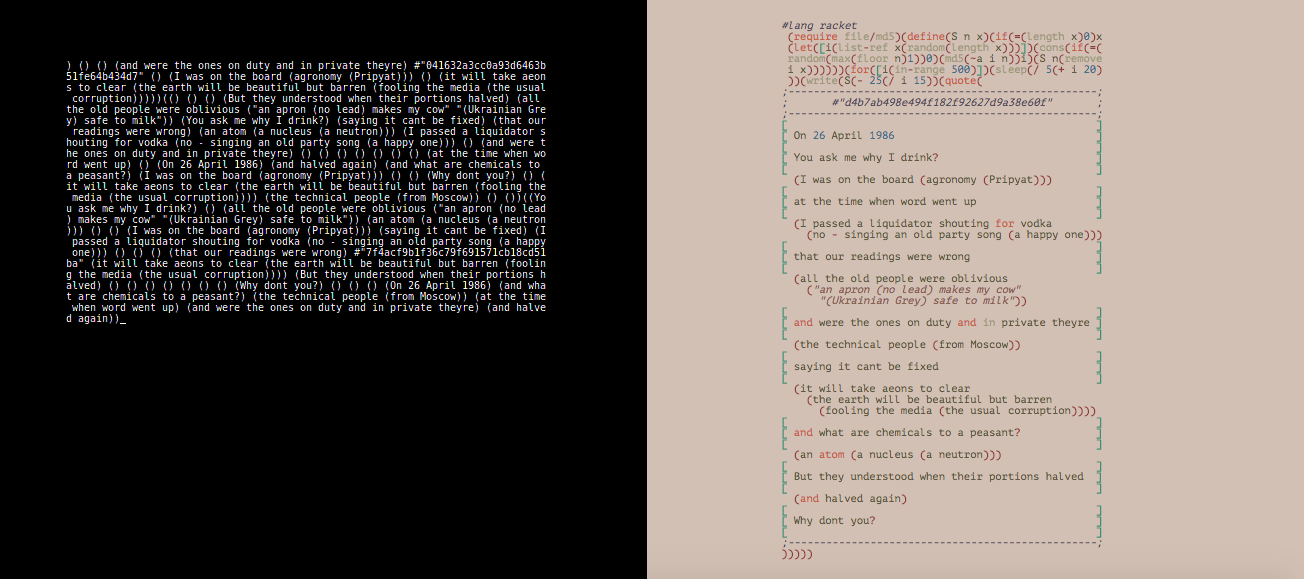

Another poem, titled “Chernobyl,” is programmed with Racket, a Lisp-like language that is known for having loads of parentheses and brackets, said Holden. Looking at the code for the program, Kerr thought it was a good jumping-off point for one of his poems. He immediately started thinking about a voice in someone’s head, someone that is having a conversation with their own thoughts. On the right, the program runs in a chaotic manner, as if someone is having an inner monologue that never quite gets to the end, said Kerr.

Kerr said there were a few occasions where Holden dabbled in poetry himself. While it might take him a bit longer to really jump into writing in some of the more obscure languages, he said he was glad the overall project gave him a sense of the “unique personalities” of the coding languages, and just a “better idea that the people who invented the languages think in different ways.”

“There are many different ways of expressing yourself and in coding for different purposes,” said Kerr. “It is functional, but that functional aspect can be linked to something that is more human and appealing, and aesthetic as well.”