Since the introduction of GitHub’s awesome new “squash and merge” functionality, there’s a whole lot more squashing going on. With UI-level access to this Git power-user feature, more teams are squashing commits to make code review easier and provide a cleaner-looking history in tools like gitk or SourceTree.

But squashing for the sake of creating a cleaner history comes along with some non-trivial downsides that are often overlooked.

Hazards of squashing

So what happens when “squash and merge” becomes policy for all incoming work, or when developers are encouraged to liberally edit their history for ease of code review?

While this can definitely make for easier code review and a more visually appealing Git history, it’s also doing two problematic things at the same time:

- Removing developmental “safety points” that can be used to locate and tactically remove any bugs that might occur.

- Obfuscating how features come into existence.

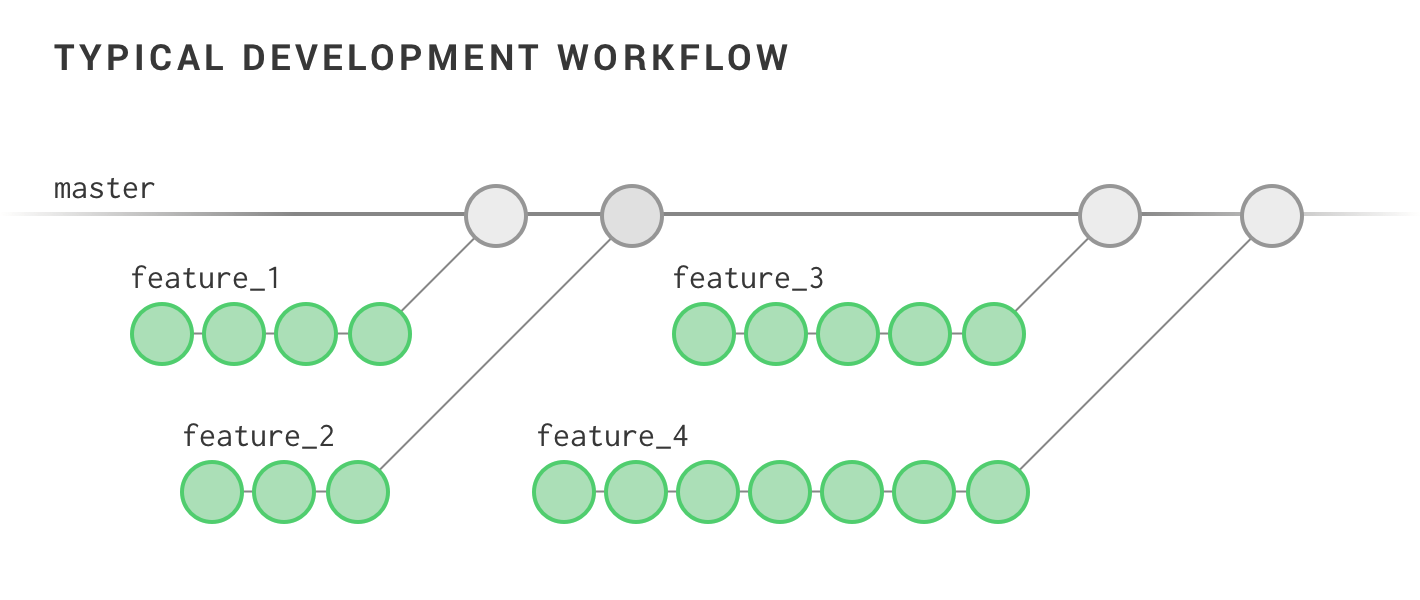

To better illustrate this, imagine a development workflow where we can see a series of iterative contributions on feature branches, followed by the merging of that work into a main branch. That might look something like this:

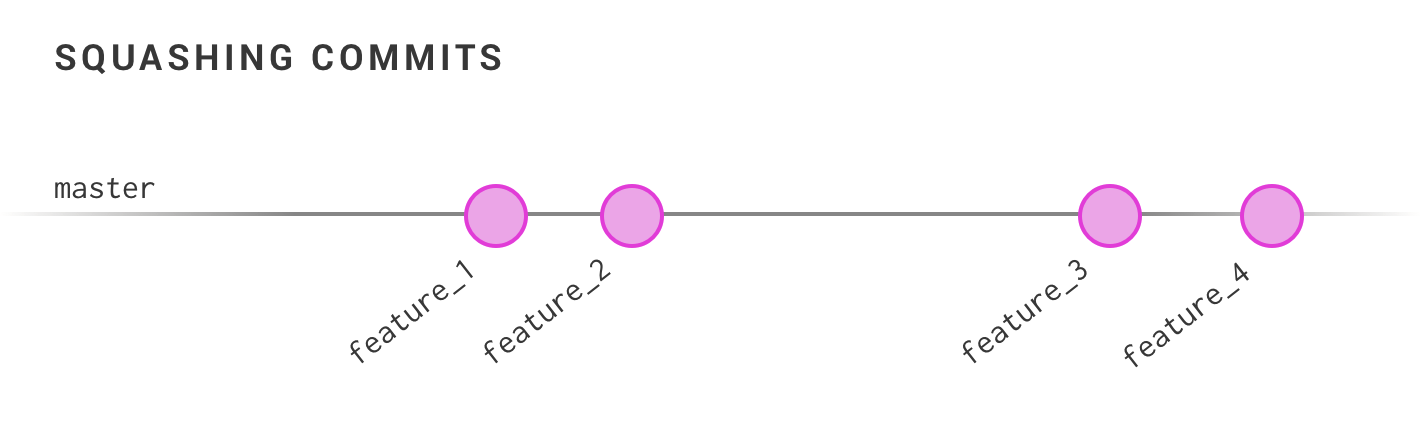

There’s a nice level of detail here: We can see features branches walking their way toward completion, followed by a merge into the main branch. Now contrast this with the type of detail you’d get on a team that automatically squashes all features as they’re merged in:

This cleaned-up view of history does make it a bit easier to focus on larger branch events, and since these commits are squashed, each one of these “final product” features can be viewed in a repo browser as a single body of work, which can be a huge time-saver.

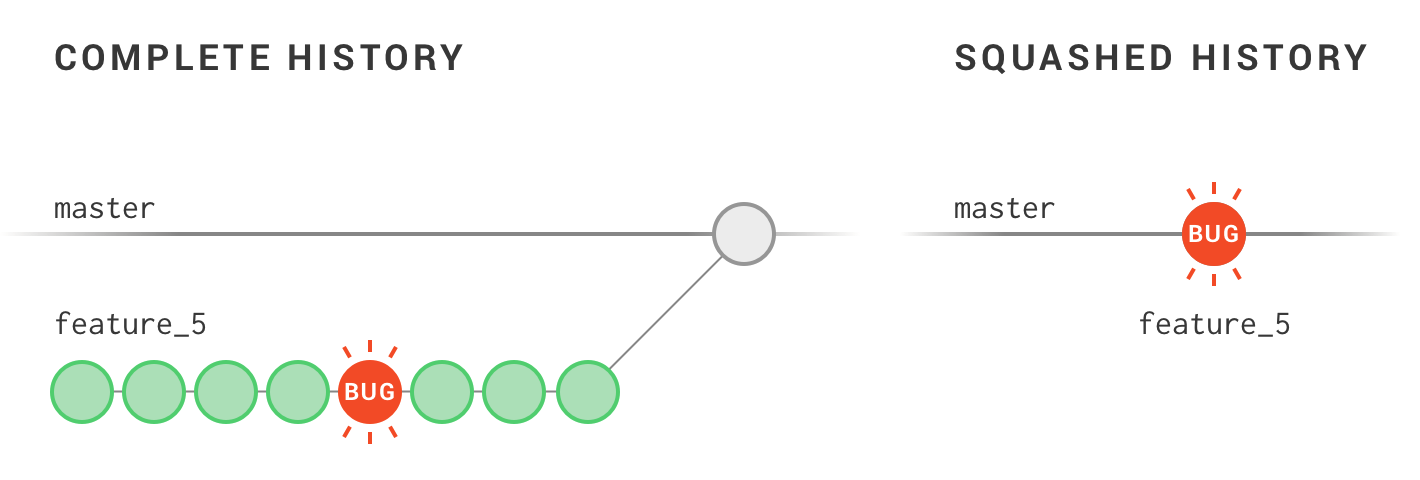

The problem here comes when we get a “bad” commit—say, a commit that introduces an undetected bug that then makes it into production. The lack of granularity in the version history makes diagnosis and mop-up problematic, effectively increasing the surface area of the problem:

In a complete history, Git bisect can more accurately narrow down the specific problem commit. The merged commit can be reverted and the bulk of the work cherry-picked into a working version in short order.

In the squashed version, bisect will tell us that the bug was introduced at some point in feature 4, leaving a fair amount of forensics undone if this is a large feature. Once the bug is located, the time to fix it could increase significantly, especially when the problem is non-trivial (as can be the case with more complex “structural” bugs).

Lack of proper version history here will make the bug harder to find and costlier to fix.

Keep squashing tactical

Part of what makes squashing a poor default practice is that it’s somewhat at odds with other things Git tends to encourage. Git as a VCS excels at helping engineers move quickly: branching is cheap, committing frequently is encouraged, and there are lots of great Git power-user features that make it very easy to recover.

So while there’s nothing inherently bad about squashing commits, and tactical squashing is a valuable thing, it’s important to remember that squashing is an inherently destructive act—one that removes development breakpoints. If overused, squashing can significantly increase the cost of finding and fixing flaws when things go awry.

(Related: GitHub ships Electron 1.0)

While a clean version history and ease of code review are important, both of these are essentially UI-level concerns, arguably better handled by development tools specific to those purposes. Taking advantage of native Git functionality can offer a non-destructive alternative: performing a “git diff master…branch” (e.g. a net diff between master and branch) will have the exact same output as a squashed commit, displaying the sum total of changes between the two branches without any permanent effect on version history.

Squashing definitely has its proper place in a Git workflow, but it’s better used as a way to clean up leftovers after an experiment-heavy implementation. Be wary of erasing version history as a regular practice; it’s a pretty invasive approach to use as a UI convenience, and can end up having hidden costs long after code is checked in.