Leave it to Finland to lead the way for self-driving car technology. While the company has no pure native auto manufacturers, it does have a thriving B2B market for parts and systems sold to automakers in other countries.

We have yet to develop reliable, fully functional self-driving cars here in America, though we are getting close. Features such as blind spot detection, 360-degree cameras, stay-in-lane assist and automatic braking in cruise control mode tell us we’re getting closer.

But one thing we haven’t been able to overcome for fully autonomous driving is what happens when rain, fog, ice and snow “blind” the sensors and cameras. This is what the Finnish self-driving technology company Sensible 4 was hoping to learn as it develops its self-driving technology called Dawn.

Sensible 4 took first place in the Dubai World Challenge for Self-Driving Transport in 2019 and the Finnish Engineering Prize in 2020. With $7 million in funding from Japanese investors, the company expects to have its self-driving vehicles on the road next year.

To make this happen, the company last December took a vehicle to Finnish Lapland to test it for two and a half weeks, in temperatures that went below -20 degrees Celsius (-4 degrees Fahrenheit). That’s way cold. The weather, the company reported, was mostly dark, snowy and cold, with snow covering driving lanes and their surroundings and visibility dropping to a mere few yards at times.

With this testing, Sensible 4 wanted to see how reliable the hardware would remain in arctic weather, to test the full software stack, and to train data gathering. These whiteout conditions, where lanes, trees and parked cars are covered in snow — along with people looking different in heavy winter clothing — were “an important aspect for the development” of the self-driving car, the company said in a statement.

Antti Hietanen, a senior autonomous vehicle engineer at Sensible 4, wrote in a blog on the testing: “For full stack testing, we had designed common scenarios from traffic, such as vehicle overtaking, emergency braking and adapting to a lead car speed. In [Lapland], we were especially interested in conducting the test while the road surface was slippery and during heavy snowfall. Both are important factors as during a wheel slippage the vehicle motion calculated based on the wheel encoders does not match to a real vehicle motion and might confuse our vehicle localization. In addition to slippery surfaces, a heavy snowfall will also impair our vision-based localization and object detection by decreasing the visibility and by deforming the landscape indistinguishable.”

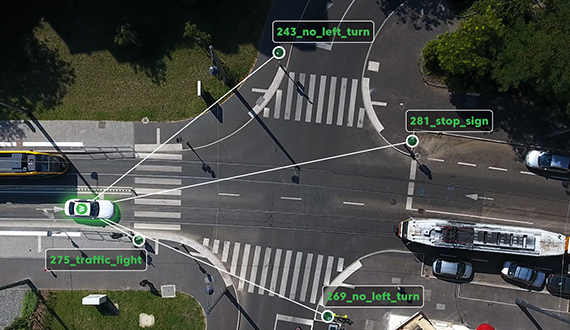

Another important part of the testing was its Obstacle Detection and Tracking System, which Hietanen wrote uses artificial neural networks for vision-related tasks. Because of the heavy data requirements for the system, he said the company had to develop “a lot of example images of objects and scenarios from realistic environments” to get the system to learn about them, to ensure it works properly.

The company found that on the hardware side, sensors faced problems in humid conditions, and when the temperature fell below -10 Celsius. Some, Sensible 4 reported, worked well, while others behaved abnormally and would require solutions such as covers.

So as the system advances from a technology standpoint, getting us ever closer to true self-driving cars, the social and cultural issues around the future of driving remain. Could a human road trip to Lapland begin to move the people side forward?