NVIDIA plans on ramping up its efforts to help developers work with virtual reality. The company has been working on virtual reality for about 12 years, and when the company first started, it was mostly in the professional enterprise space, with large immersive display environments.

Of course, with the recent boom of consumer headsets from companies like HTC and Oculus, NVIDIA has refocused its efforts, and over the last few years the company has been thinking about how it can improve its GPUs as well as its SDK for supporting VR experiences, said Jason Paul, general manager of virtual reality for NVIDIA.

NVIDIA recently released its flagship gaming card called the GeForce GTX 1080, which is built on the latest Pascal architecture. While it delivers new performance and power efficiency, it also includes VR capabilities.

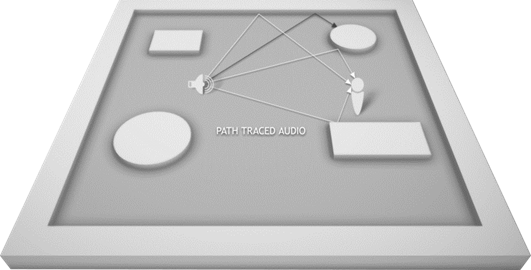

NVIDIA also plans on tackling other aspects of the VR equation with its VRWorks suite of APIs, libraries and engines that help developers create virtual reality experiences. Its new audio SDK allows for ray-traced audio, which is a technique that tracks the path of light or sound and simulates that in a virtual environment.

For example, if a virtual environment is set in a small room, then the sound should emulate the physical environment correctly, according to Paul.

“Sound in a small room will sound different from sound in a big room, in a virtual room,” he said. “The point of it is, with VRWorks Audio, your virtual audio will reflect your virtual environment.”

In a recent press conference before Computex, CEO of NVIDIA Jen-Hsun Huang talked about the challenges of VR and how the industry is 20 years away from solving some of them. One major challenge of VR lies in the displays themselves: They need better resolution, and developers need to get the VR worlds they create to behave according to the laws of physics.

Since this is the first generation of consumer VR headsets, it’s easy to get caught up in the industry hype, but Paul said that that developers are still in the beginning stages of consumer class VR headsets, and “there is tons of room for improvement.”

VR displays need a higher resolution so users do not have the “screen door effect,” where visible lines between pixels on a display give users the feeling that they are looking through a screen door, impeding their view.

Paul also added that headsets need higher refresh rates to be more comfortable for the user. Most headsets and displays have the users’ eyes focus at a single depth, which can cause eyestrain.

Other areas that need focus include better optics and display, and the headset themselves should come down to more of a sunglasses look rather than ski goggles, according to Paul.

VR headsets should also a larger field of view so the virtual environment encompasses the full range of vision. And looking across every aspect of the VR ecosystem, there are plenty of other areas of improvements, said Paul.

Whether these challenges will still be around in another 20 years or so is just speculation, but Paul said that it could take that long just to “draw the same number of pixels that you do today” and to match the quality of human vision.

What NVIDIA plans to do to speed up this long process is create faster processors that will be used to power the headsets, and that can power more pixels and high-resolution displays.

“Things will continue to improve, things will get better, but there’s a long road map for improvement,” said Paul.