As Steve Ballmer’s tenure at Microsoft comes to an end, with Satya Nadella taking over in his place, former employees and analysts are beginning to write the final word on his legacy.

Ballmer ascended the throne of Microsoft in January of 2000. When he took over as CEO for Bill Gates, Microsoft was bringing in US$21 billion in revenue and the company’s stock had just hit an all-time high of $51.87 a share in September 1999. The Windows desktop OS was atop the personal computing market, and Internet Explorer was the leading Web browser by a mile.

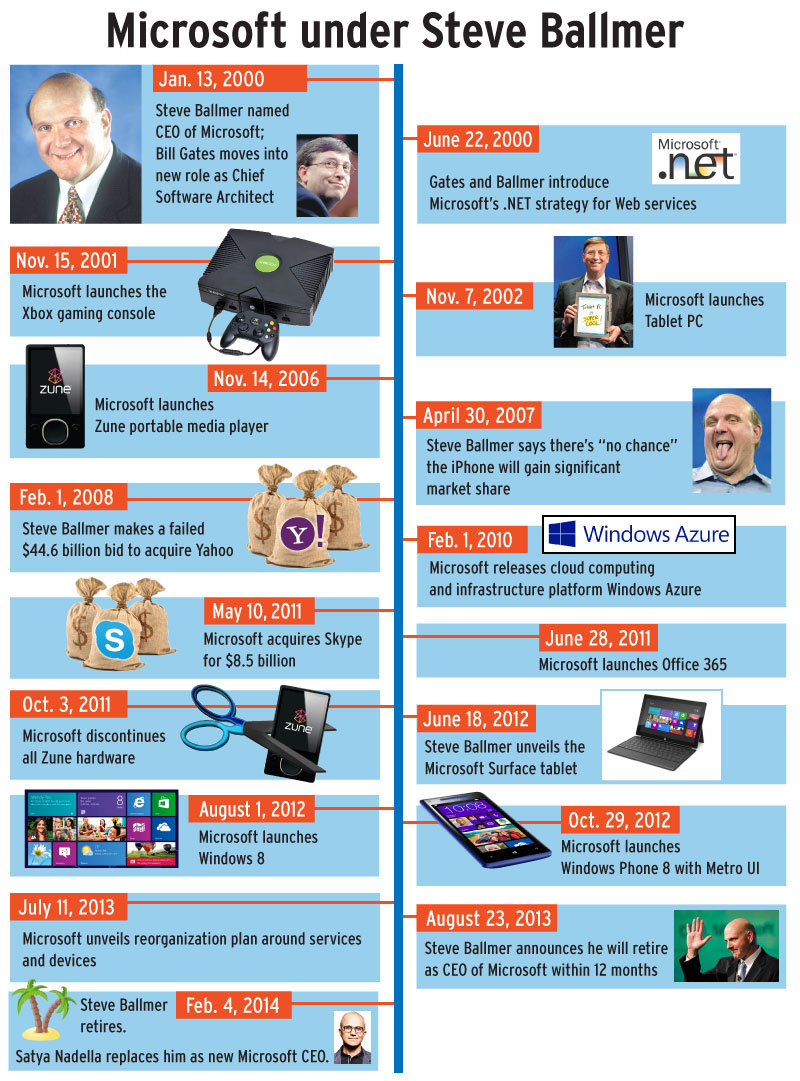

Over the next 13 years, Ballmer left his stamp on Microsoft with bold product and management strategies, high-profile successes and failures, and a loud, bombastic personality that spawned many a viral video. The greatest (and worst) hits include everything from Windows Vista, the Zune, Bing and the Surface RT to Windows Phone 8, Office 365 and Windows Azure.

In August 2013, Ballmer announced his impending retirement from a very different Microsoft than he inherited. During his tenure, Microsoft created 16 billion-dollar businesses, and in 2013 the company pulled in revenue of $77 billion. Though if an 8% stock surge to almost $35 a share after announcing his retirement is any indication, Ballmer leaves Microsoft with a decidedly mixed legacy.

What Ballmer did right

Under Ballmer, Microsoft invested heavily in enterprise software, including a database, development platform, operating system, and e-mail and collaboration platform. The company took the Microsoft Office suite, along with hosted services such as Lync and SharePoint, and put them all online as part of Office 365.

“When Steve Ballmer took over, Microsoft’s share of enterprise software was tiny,” said Ted Schadler, VP and principal analyst at Forrester Research.

He highlighted the increase in Microsoft’s business software revenues from $10.4 billion to $47.9 billion between 2000 and 2013, an increase of $37.5 billion. For comparison, he pointed to IBM, which grew its business software revenues by only $12.8 billion during that time.

“Microsoft is now one of the biggest suppliers of business software, competing with IBM, Oracle and SAP,” Schadler said. “This happened because of a strategic focus on quality software, a direct sales force, and pricing that made it easy for companies to get started.”

Microsoft also established itself as one of the leading cloud providers under Ballmer’s leadership. The Windows Azure platform is still a distant second to Amazon Web Services in terms of market share, but in the increasingly competitive world of cloud computing and virtualized infrastructure, the revenue of Microsoft’s PaaS and IaaS offerings is seeing uninterrupted.

“Ballmer saw some of the changes, said we’re all in with cloud computing, and made a big commitment,” said Gartner analyst David Cearley. “We were all pretty skeptical initially, but if you look at what they did with Azure, over the intervening time they actually delivered on that message of shifting things to a cloud-centric model and a variety of Web technologies.”

There’s one other space besides the waning PC market where Microsoft emerged and remained a leader during Ballmer’s tenure: gaming. In the past decade Microsoft’s Xbox 360 surpassed Sony’s PlayStation 3 in popularity, while introducing Kinect to keep pace with the Nintendo Wii. Microsoft sold more than 102 million Xbox and Xbox 360 consoles during their runs, and Xbox Live still boasts more than 46 million subscribers. Xbox One sales have been underwhelming thus far, but it’s early going.

Big bets, big duds and missed opportunities

Steve Ballmer’s biggest blunder as CEO (which he admitted was his greatest regret) is Windows Vista. The six-year period from 2001 to 2007 dominated by the ill-fated Longhorn-turned-Vista project drained company resources and devoted the time and effort of key Microsoft personnel to an OS that turned into an unmitigated disaster.

Widespread criticism of seemingly every aspect of the overhyped Windows XP successor landed the moment it hit the market, and Ballmer conceded that the release of Windows 7 two years later was largely a way to fix the fundamentally flawed product.

One place those sidetracked Vista developers, engineers and resources would have been far better spent is in expanding Microsoft’s mobile presence several years earlier. Ballmer’s foolhardy dismissal of smartphones didn’t help either.

In March 2009, three months before the iPhone debuted, he said, “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share. No chance. It’s a $500 subsidized item.”

As of August 2012, iPhone sales eclipsed the sales of every Microsoft product on the market combined. By that time, Ballmer and Microsoft had finally decided to get in the game, but the release of Windows Phone 7 in 2010 and the redesigned Windows Phone 8 in 2012 came far too late to seriously compete with iOS and Android.

To Microsoft’s credit, Windows Phone is clawing into the race, but still sits at less than 5% market share in the U.S. and 10.8% in Europe as of November 2013. It’s too early to know whether Microsoft’s Nokia acquisition might turn the tide.

Microsoft’s mobile development under Ballmer is rife with late turnarounds and squandered opportunities, and the Surface RT is another example of that. Released a full two and a half years after Apple’s iPad was established, the Surface struggled to sell despite a heavy ad campaign, substantial price cut and a largely positive reception to the device. Piles of Surface tablets, Microsoft’s first-ever device made with its own hardware, sit unused because he simply wasn’t quick enough on the draw. In the cases of smartphones and tablets, Microsoft simply didn’t think big enough until it was too late.

“Microsoft was actually a very early innovator with smartphones and tablets, before many people,” Gartner’s Cearley said. “But they saw it as, ‘Let’s put Windows on a phone!’ They didn’t think about how to reinvent the experience and do something different that might even challenge Windows. They were trying to essentially extend those existing products versus rethinking and innovating with it.

“Then you had companies like Apple come in that did think about design and reinventing things, and they launched the market. Under Steve [Ballmer], Microsoft was very early with technical innovations, and very late with design and user experience innovations in some of those key markets.”

Another misguided decision motivated by competition with Apple was the infamous Zune, Microsoft’s portable MP3 player.

“Zune was a direct Steve Ballmer decision,” said Rob Enderle, principal analyst at the Enderle group. “Now, it wasn’t the decision itself that was bad, it was the lack of analysis and oversight that resulted in a failure. We’ve seen Samsung with the Galaxy line go directly after Apple in the same way Microsoft did with Zune, albeit on tablets and smartphones, and be successful through adequate resourcing.

“Ballmer’s mistake was to run at the iPod head on and not adequately assure the team making the effort was going in the right direction or had enough resources to be successful. The failure of Zune was one of the most damaging failures during Steve’s tenure.”

Say what you will about Ballmer, but he’s never been afraid to bet big. A complex example of that exuberant spirit is Bing, which hasn’t quite been a failure but certainly can’t be considered a success.

Ballmer made no secret during his tenure of the desire to challenge Google in the search-engine market. After a failed $44.6 billion bid to acquire Yahoo, Microsoft launched Bing in June 2009. Bing was his baby. He evangelized Bing to no end, and spent hundreds of millions of dollars and product development resources on it, and it worked… just not nearly as spectacularly as his effort would suggest.

As of July 2013, Bing had carved out a 17.9% search share, finally getting Ballmer that No. 2 spot he initially coveted. Yet Google is still on top at 67%, with Microsoft, just as it is with mobile, lagging far in the distance.

A different kind of CEO

Steve Ballmer is about as different from Bill Gates as two CEOs can be. Gates is the soft-spoken technical visionary who founded a company that changed the world with the PC. Ballmer is the loud, energetic businessman who diversified and expanded Microsoft into a tech giant. He’s emotional, charismatic, and has been known to run onstage at Microsoft events screaming at the top of his lungs.

“Ballmer brought very much of a business focus as CEO. He’s the ultimate marketer, the ultimate salesperson,” said Cearley. “He brought a very significant business rigor and a focus on products and business units that could drive revenue. But within that is a significant challenge resulting from Steve’s style. It doesn’t encourage out-of-box thinking, things that are maybe more tenuous bets that don’t have a detailed business plan.”

Ballmer’s business-minded philosophy, of always looking for that next billion-dollar business, drove significant revenue and profits, but stifled the sorts of projects that have popped up from startups and even companies like Google. Microsoft project managers began to look for incremental additions to protect existing businesses, and in so doing industries such as mobile and search were neglected.

“There’s a huge gap in the Ballmer era between what can be if you rethink and reinvent things, and what actually gets out into the products,” Cearley said. “Microsoft has often been a very early innovator from a technical perspective, but they’ve generally not been an effective innovator from a design and a user experience perspective.

“I think that’s Ballmer’s biggest blind spot. Steve gets the business. Steve understands the technology and surrounds himself with technology experts. He does not get importance of design like Steve Jobs did, and it’s really firing through the industry right now.”

That same business mindset also had a profound effect on Microsoft’s internal culture and management structure, as Ballmer introduced strategies like stack ranking (also known as the “Vitality Curve”) to drive better employee performance through individual productivity grades and competition that determines compensation. Microsoft first adopted the policy in 2006, and in 2011, despite criticism and largely negative employee sentiment, Ballmer sent an internal memo announcing an outright shift to the Vitality Curve. In November 2013, three months after he announced his retirement, Microsoft abandoned the system.

“[Stack ranking] happened before he took the office and was consistent with what other firms did after reading [about] how Jack Welch turned around GE,” said Enderle. “However, no one realized that like a medication targeting a particular disease, forced ranking doesn’t make healthy companies stronger. It weakens them, turning employee against employee and making collaboration nearly impossible. Toward the end of Steve’s reign he reversed this decision, but too late to save his job.”

Ballmer’s unique brand of management and outspoken demeanor have made a deep imprint on Microsoft, and while a great many employees have come to respect and appreciate his way of doing things, other key pieces have been unable to coexist. Enderle believes Ballmer’s refusal to use Microsoft’s internal PR resources and his inability to work with chief software architect Ray Ozzie were two mistakes stemming from his personality.

“When Steve took the job initially, Bill left him with two key resources: A marketing and PR organization that could convey Steve’s side of any story, and Ray Ozzie, who could do the things Steve wasn’t good at that Bill did,” said Enderle. “One protected Steve’s image, and the other assured that Bill’s departure wouldn’t leave a hole in the firm. Steve effectively shut down corporate marketing and PR and lost control over his image early on, and he couldn’t work with Ray Ozzie whom he seemed to see as a threat to his authority. Thus he wiped out two of the most powerful mechanisms assuring his success.”

Yet that same overpowering persona and exuberance are part of what made Ballmer’s tenure at Microsoft unforgettable. Arguably no one, save for Gates, might care more about Microsoft as a company than him. He was Microsoft’s 30th employee, hired in 1980. Soon after taking over as CEO, he navigated the company through an antitrust lawsuit by the U.S. government and class-action lawsuits from other companies that ruled Microsoft an “abusive monopoly.” The ruling was ultimately overturned and Microsoft remains intact.

Dave Mendlen, now the CMO of Infragistics, worked at Microsoft from 1998 to 2011 in various roles such as senior director of Windows Product Management and senior director of Developer Product Management and Marketing. He also served as Gates’ and Ballmer’s official speechwriter just after the latter took over as CEO.

“I was fortunate enough to have spent three years at Steve Ballmer’s side shortly after he took the reins of CEO at Microsoft,” Mendlen said. “At the time, we were imminently waiting for the DOJ ruling to come down. No one knew if the company would be broken up or penalized in some other way. Steve was nervous and angry—nervous in that he didn’t want anything to change this company that he loved so much and angry that he had no real ability to change the outcome of the ruling.

“Later, now through the dark times, I was working with him as he drove the acquisition of Great Plains Software. It was the biggest acquisition that Microsoft had ever done, and Steve knew that he was doing something big. He was both publicly confident and then privately introspective—was he making the right decision? Would this drive the company in the right direction? He was asking himself and a few folks around him these questions. But you could see that Steve had a burning need to drive the company to its next plateau.”

Mendlen worked with Ballmer on one of his more famous speeches, which opens with a video of Ballmer spoofing “The Matrix.” Whatever Ballmer’s legacy as Microsoft CEO turns out to be, for better or worse, speeches like that exude a larger-than-life personality that the company will not likely see again.

“I had worked with the Wachowski brothers to have them help me do a spoof of the Matrix video to kick off the speech,” Mendlen said. “Steve rose from the under the stage dressed as Neo and kicked off an amazing speech that ended with a church choir singing ‘Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.’ That speech scored the highest of any speech Steve had delivered on record. And that is the magic of Steve. He infected the passion of the company into me and in everyone he worked with. Steve Ballmer is the only CEO that annually runs around high-fiving his employees at the annual meetings. Microsoft will miss that passion. I already do.”