We have seen this movie before: In the 1990s (to be precise), after IBM and Microsoft invented the PC and after Apple redefined it graphically with the Mac, PC market shares started to take a decided turn toward Windows PCs. We have been living in a 90%-plus PC market ever since.

The key driver for this network effect of device adoption was the software and hardware ecosystem that developed behind the PC. Strategists everywhere have since observed similar effects in technology adoption in other markets, dissecting this PC history to try to divine how mobile platforms are likely to evolve. In fact, such sticky network effects are what many vendors are trying to achieve by positioning themselves as platforms.

Vendors love platforms because platforms generate ecosystems, and ecosystems make technology adoption durable. Platforms are vessels for applications, and so to create successful platforms, a strong software ecosystem is essential. Birthing a platform requires a virtuous cycle of a growing user base and a growing application base that is built to monetize the user base, which in turn attracts more users to the platform. Where does Windows Phone sit in this dynamic?

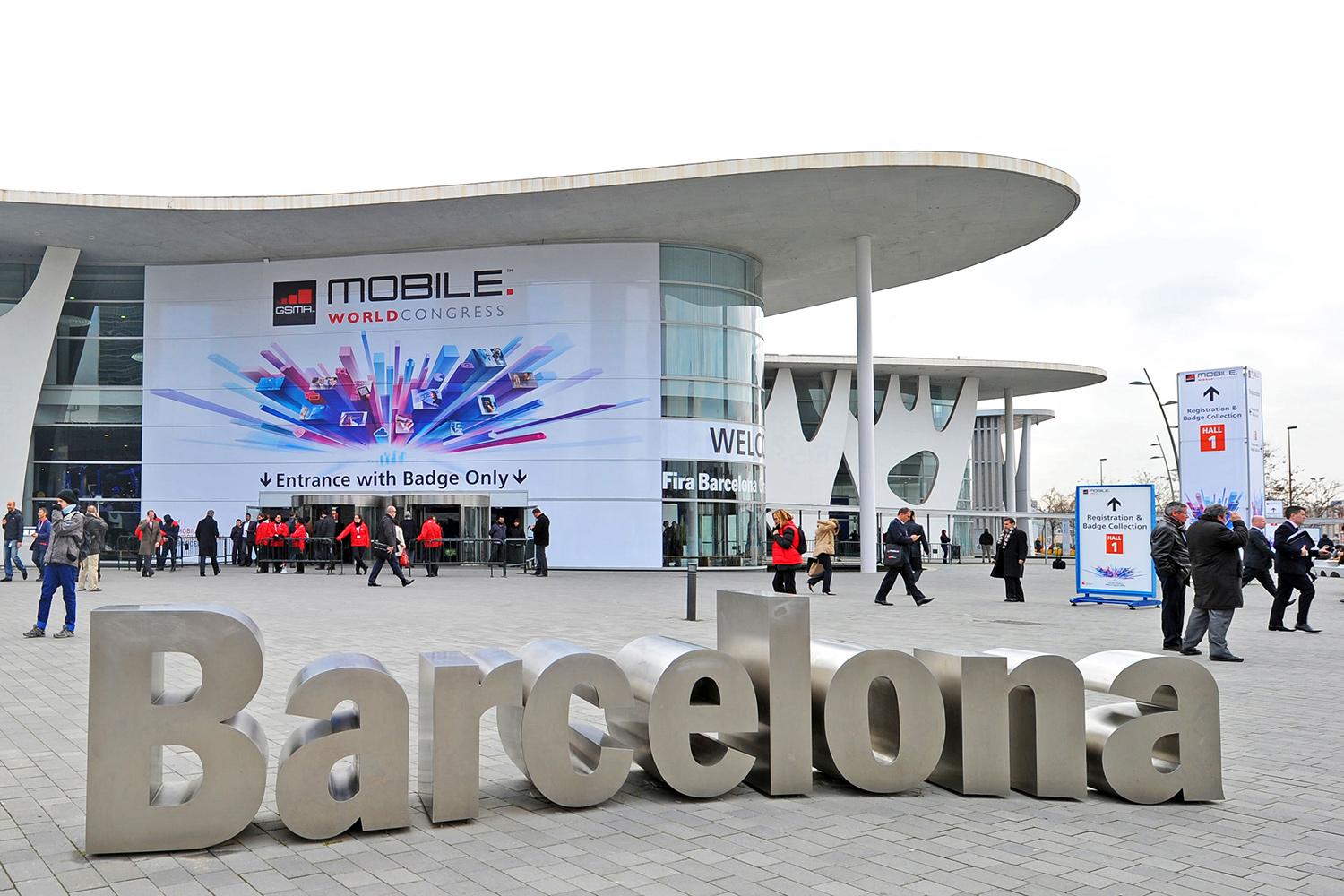

The state of the market

Windows Phone has been making slow but steady progress, having recently passed BlackBerry in quarterly shipment numbers. According to the latest IDC data, market share for the first three months of 2013 show Android running away with 75% of new shipments, with Windows Phone edging out BlackBerry at 3.2%. The iPhone captures most of the balance at around 17.3%.

These numbers show the outlines of similar ecosystem dynamics to the early years of the PC market, but the smartphone market is potentially an order of magnitude bigger. It stands to reason that there could be more than two surviving players. History often repeats itself, but rarely in the same way.

As the smartphone market matures, it shows signs of both consolidating and diversifying at the same time. Mozilla has birthed a new mobile OS and shipped phones with a couple of carriers. Samsung has promised to produce Tizen phones as it winds down its Bada proprietary smartphone platform, a victim of the ecosystem war. Nokia continues to make its Asha line of phones smarter, pushing its unique low-end app ecosystem. Finally, BlackBerry has launched a couple of new devices on its promising new platform, and intends to fight hard for third place in the ecosystem wars.

#!

The app economy problem

Windows Phone claims about 150,000 apps today, a fifth of what iOS and Android feature. To deal with the app gap, Microsoft has focused on recruiting flagship apps, pointing out that quality is what matters, not quantity.

But in reality, both matter. While some major apps are still missing (e.g., Pinterest and Hulu Plus), others have recently come to the platform (e.g., Tumblr, Spotify and Pandora). Some apps like Pandora were available early for Windows Phone 7 but have taken longer to come to Windows Phone 8. Others are coming without taking full advantage of some of the distinguishing UI features of Windows Phone 8.

The key issue for the Windows Phone platform is the long tail of apps that are the byproducts of the transforming digital economy. Windows Phone has to recruit not only the major airlines, retailers and banks, but also local credit unions, government agencies and restaurants. All manner of merchants and manufacturers are increasingly finding it essential to engage their customers with apps to establish loyalty and improve customer service. The app economy, characterized by the phrase “There’s an app for that,” is exactly about such apps.

Yet, developers are overwhelmed with too many platforms and tools. If they come to Windows Phone, they may ignore its unique style and deliver apps that clone their other platform efforts. It is instructive to summarize some of the road map and execution challenges the platform has faced.

Platform fragmentation

App growth was off to a running start in the early months of the Silverlight-oriented Windows Phone 7. That growth slowed considerably with Windows Phone 8’s transition to the new OS kernel and app model. While old applications were cloud-compiled to run on Windows Phone 8 devices, developers had to rebuild their apps in order to evolve them strategically for Windows Phone 8. The transition was also announced some six months before the arrival of Windows Phone 8 devices and the delivery of the new SDK.

Concurrently, the Microsoft client division was ramping up developer evangelism for the big Windows 8 evolution of the PC. The result was a developer fragmentation problem that has persisted: Should developers continue to target existing Windows Phone 7 devices with Silverlight, wait for the Windows Phone 8 model to be clarified, or invest in Windows 8 tablet development?

Many did none of the above and focused mobile development on iOS and Android. In fact, developers are watching the evolution of the Windows client platform—and in particular its extension to smaller screen sizes—and are wondering if yet another transition is in the air to converge the UI of Windows and Windows Phone.

The Windows Phone app problem is tangled up with the overall story of Windows convergence. To adopt the platform at scale, developers will need a clearer road map and a rapid cycle of predictable device innovation that takes them to the converged ecosystem promised land with minimal delay.

Because the party is not over, Windows Phone still has the