Achieving DevOps—a continuous, collaborative product delivery cycle that incorporates software development and IT operations equally—is an elusive goal for many enterprises. Even after agile software development practices have revolutionized teams, the fundamental motivational mismatch between developers and sysadmins often persists. Development is feature-driven. Operations is stability-driven.

Netflix, Google or Facebook aside, how do real-world enterprises get these two groups to collaborate at the symbiotic level advocated by DevOps? We spoke with two evangelists for Red Hat: Markus Eisele, a developer advocate based in Germany, near Munich, and Burr Sutter, product management director for developer products based in Raleigh, NC, to get their perspectives on how enterprise DevOps can best gain traction.

SD Times: From your vantage point as an ISV, what is the most common mistake in trying to achieve DevOps?

Sutter: The No. 1 mistake I see IT organizations, shops and developers make is often they’re looking for a tool to come in and solve their problems. There are tools that help, but in general it’s about cultural change, workflow and process change.

Eisele: Enterprises in general don’t actually see what it means to do DevOps. To them it’s a solvable problem by tool. We have seen independent software development teams and internal IT organizations working together in waterfall-driven processes for years. When people jumped into agile, they said, “Let’s see if we can get the stakeholders closer to each other,” but that never included operations. The whole problem goes all the way up the organizational chain. Getting those cross-business-unit methodologies to work together is not solvable by a tool. And when vendors say, “We are going to sell you containers and microservices so you can achieve Continuous Delivery,” the part they don’t mention is the cultural change.

SD Times: John Willis used the acronym CAMS, for culture, automation, measurement and sharing, to define DevOps. The automation practices rely on tools that are increasingly common for Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery. What’s wrong with getting the automation going and calling it a day?

Sutter: Your automation is a set of tools: Jenkins, Gerrit, GitHub. They form an automation chain. But the challenge is, they can’t make the culture change. As Willis said, “People and process first. If you don’t have culture, all automation attempts will be fruitless.” The key word you hear in the DevOps space is “empathy.” You have to be able to collaborate well together.

In the average IT shop, your code goes to production every nine months. The code you create has zero value until it goes into production. More importantly, you as a developer can actually learn things once your code goes into production. Many joke that “Our end-users are our testers.” The goal is to make enterprise software development get things into to production faster. Maybe it’s a month, maybe more, maybe less. It’s about lowering that interval to get feedback.

Eisele: An IDC report from last year found that, prior to implementing DevOps, 63% of teams were releasing one or two times a year, 27% were doing quarterly releases, and only 7% were releasing monthly. Of course, they were predicting those release rates would increase dramatically in the next two years, once DevOps was going strong.

Sutter: I talked to one team, and they go to production about every two years. A lot of enterprise shops are on multi-month cycles. If you go to production every nine months, are you making babies or are you making software? Our former CTO, Brian Stevens, went to an enterprise IT shop and asked, “What does it take to get ‘Hello, World!’ into production?” It took 30 days. Where is your organization on that spectrum?

I wonder if that’s not a theme we can hammer on for a while. What would it take to get “Hello, World!” crafted, built, tested and deployed out the door?

Eisele: I wonder if that should be a benchmark: The “Hello, World!” benchmark of DevOps. It’s incredibly hard. You’ve got to identify the various project types and deliverables (war, tar, images). You’ve got a variety of different people writing different codes—for example. database migration or staging. Maybe projects need to update the Content Delivery Network (CDN) Server. There’s just no single path you could just measure. The variety is huge.

SD Times: And even harder to measure if you have a containerized workflow?

Sutter: Oddly enough, many folks think that if they simply adopt Linux containers then they also have started DevOps—containers are just another tool.

Eisele: Containers would make it easier at the end of the day, but that’s not a common scenario yet. We know how many people are running containers in production today: roughly 6%.

SD Times: Who are the culture gurus you recommend for enterprises trying to make these deep-seated changes?

Sutter: Personally, I love Neal Ford from ThoughtWorks; he’s a friend of mine. He did a lot around agile back in the day, and has talked about DevOps and microservices. I also like the guys behind the DevOps podcast: John Willis and Damon Edwards.

Eisele: Another ThoughtWorker, Sam Newman, is great. He has more insights about microservices. Daniel Bryant has a consultancy in the UK. They do quite a bit on the soft-skill, people-skill side of DevOps.

Sutter: Speaking of soft skills, I did a presentation for architects many years ago. It was all about how to adopt open source. The developers would say, “Yes, but so-and-so won’t let me adopt it.” They also pointed out that their DBAs at that time were a huge bottleneck. So I asked, “Well, have you ever taken a DBA out to lunch?” They were stunned. They were like, “Oh, that might fix it!”

Eisele: Everyone is talking about full-spectrum development. The reality in enterprises is there are specialists for everything. DBAs are a perfect example. Cutting enterprise development into front end and back end is not helpful when it comes to DevOps. One particularly interesting thing about enterprises is that you might have 200 developers in a project. That is a normal setting for enterprises. Now, ISVs are used to driving that sort of project, but many enterprises can’t run an agile project at that size. There are many ways to make that easier. DevOps practices are not necessarily scaled to the level enterprises need them, though, so this is not going to help either.

Sutter: So, Markus, that’s where microservices come in: Break it into pieces.

Eisele: This is where a solid software architecture is the foundation for everything. How you actually structure your project, structure your code. Today we’re starting to see why you can’t let it slip. Especially when you’re building a microservices architecture.

Sutter: One thing we’ve said a lot internally at Red Hat is that DevOps was born from open source. The primary tools that people are using to drive their DevOps initiative are from open source. The cost of the tools used to be a huge barrier to entry for adoption 15 years ago. It’s also about the open-source culture. If you look at open-source projects, they are inherently distributed and highly automated, with proper version tracking, build, test and deployment automation.

In a June 2015 IDC survey, 82% of respondents said open source enables their DevOps strategy, for multiple reasons: It improves productivity for both Dev and Ops, it speeds up business innovation without vendor lock-in, it’s easy to customize, and you gain access to supportive, innovative open-source communities.

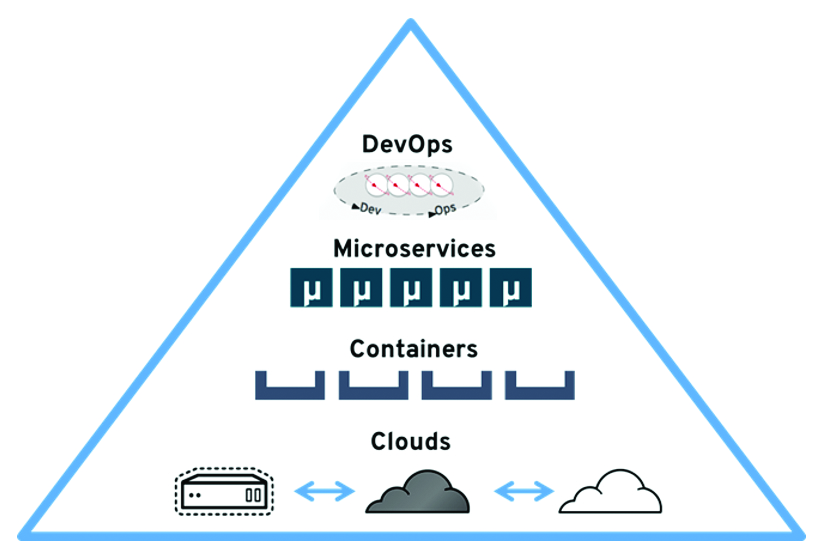

Eisele: The one thing I really learned to love about open-source communities and especially about the JBoss community, is that they have a great ability to embrace a lot of different skill sets. The way those communities are building software is very much the model for most companies today. The pyramid of modern application development (which can be found in my free O’Reilly Mini-Book, “Modern Java EE Design Patterns: Building Scalable Architecture for Sustainable Enterprise Development”) captures the whole challenge that Enterprises have to address these days. DevOps is at the top of the pyramid.

Sutter: So many people are looking for silver bullets: They think Netflix OSS will cure their problems, or containers or microservices will. But not one thing will create a DevOps culture. Instead, grab hold of some of the cultural tenets, like defining infrastructure as code, treating servers as “cattle, not pets,” and prominently displaying metrics such as cloud health and Continuous Integration events. And then make sure to spend some time in genuine, face-to-face interaction with people outside your silo. That’s culture change.